Dervish Traditions in Turkey – Tombs II

Tombs are very important in Dervish traditions in Turkey and elsewhere. One tomb I particularly love is in a suburb called Merdivenköy, also on the Asian side of Istanbul. Today this is a heavily built up residential area but the suffix köy, meaning village, points to its history. During the reign of the Ottoman sultans the palace was supplied with milk, cheese and yoghurt from dairies here.

In the past, there was also a dervish order to which the Ottoman Sultan Beyazit 1, nicknamed ‘lightening’, belonged. He laid siege to the city of Constantinople in the late 14th century, holding it to ransom until defeated by Timur. Later on he was martyred on the Ziverbey road (modern day Minibus Street) at Çemenzar, a suburb that abuts Merdivenköy. Beyazit is believed to have been interred in a grave marked with cypresses, next to a sacred spring, on a hill called Namazgah.

The Ottomans named him ‘gözcü baba’, the watchman, or lookout, meaning the one who spied on the Byzantines. More generally it is taken to mean the one who watches over the city in honour of his past deeds. No such grave exists here today but the neighbourhood is still known as Gözcubaba.

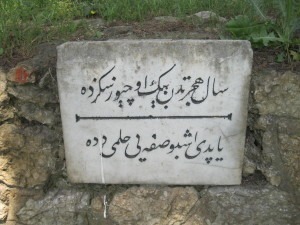

Today, a stand of cypresses still exists at the intersection which marks the start of Gözcubaba. On the low wall surrounding them a marble slab, inscribed with Ottoman Turkish marks the spot. I had a friend ask their Ottoman language teacher to translate the inscription on the stone.

I’m told it reads, ‘This hall was built 1308 years after hijra, Hilmi Dede’. Hilmi Dede was a Bektaşi dervish born in the Göngörmez neighbourhood of Istanbul, close to Sultanahmet in 1842. He was posted to the Istanbul Sultan Şahkulu Dervish lodge in Merdivenköy in 1864 and spent the ensuing years developing it. Hijra is the journey of the prophet Muhammad and his followers from Mecca to Medina. It is used to set the first day of the Islamic calendar and roughly corresponds to July 622 in the Georgian calendar.

According to the tabular Islamic calendar 1308 years after hijra would have been 1891 AD. I take this to mean that Hilmi Dede was instrumental in founding a lodge (the word ‘hall’ is sofa in Turkish, meaning a long room with rooms opening on to it) on this spot at that time. When he died in 1907 he was buried in the winter courtyard of the dervish lodge and later on his relatives built a special garden in his memory in Gözcubaba.

Just down the hill from this spot is my other favourite Dervish tomb, ringed by a green fence, sitting in the middle of a busy road that feeds on to a major highway. In order to reach it I had to dash across the road while looking madly in all directions because no one obeys the traffic rules here. Another pedestrian took advantage of my courage to make the crossing too. Unlike me, she had come to pray and quickly entered the enclosure where she began her supplications.

This tomb is dedicated to two dervishes, Mah Baba and Gül Baba. The first name Gül Baba, is well known in history. Originally named Cafer, he was an Ottoman Bektaşi dervish poet who was a close companion of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent. Gül Baba originally came from a village in Sivas, but is thought to have died in Buda, Hungary, during the first Muslim religious ceremony held after the Ottoman victory in 1541.

Others believe he was killed during fighting below the walls of the city on August 21 in the same year. Regardless of the circumstances under which he died, Süleyman declared Gül Baba patron saint of the city and is believed to have been one of his coffin bearers. His actual burial site is in an octagonal türbe in Mescet Street in Budapest. It was converted into a Roman Catholic Chapel in the 17th century but was still accessible to Muslim pilgrims until the 19th century.

Then, in 1885, the Ottoman government commissioned a Hungarian engineer to restore the tomb. When the work was completed in 1914, it was declared a national monument. The site was restored again in the 1960s and the 1990s and is now the property of the Republic of Turkey.

I could find no information about Mah Baba, and the little information I did find out that is specific to this particular tomb comes from İsmail Tosun Saral, a writer and expert on Turkish Hungarian relations. He writes that another Gül Baba lies here, on the right hand side of the road from Merdivenköy to Uçgöztepe.

Saral quotes from Dr Bedri Noyan Dedebaba, respected dervish and researcher of Alevi and Bektaşi history, who states this Gül Baba died in a battle between the Ottoman Turks and the Byzantines in June of the year 1329 (Gregorian calendar). Whatever the real story behind this tomb, I know the woman praying at the graveside believed her wishes would come true. I like it because it stands as testament to the way progress has bend to tradition, just in case the long held beliefs about these tombs are true.

You can find more on dervish traditions and Turkish tombs in Istanbul in the complete version of this essay in the second edition of my book, Inside Out In Istanbul: Making Sense of the City