Ferikoy Protestant Cemetery

Around once a month I travel by Marmaray and Metro to a small tekel (bottle shop) in Kurtuluş to buy wine. They have a good selection, the man who runs it is nice and even with the cost of my transport fares, their wines are cheaper than anywhere I’ve found so far in Kadikoy, near where I live in Istanbul.

I’m a creature of habit so for many months I followed the same route after getting off the train. After emerging on the street I walked up a hill past a high stone wall and followed it left around a corner, before turning left again. I basically walked three of the four sides of an enormous square, and each time I did, I passed the entry to the Ferikoy Protestant Cemetery. It was during the time of strict Covid restrictions and the gates were locked. A sign on the bars said to ring for entry but I often feel quite shy in situations like that so I didn’t.

One day I took my courage in my hands and pressed the button. A friendly man, the father of the family living on site, let me in. He welcomed me and went back to help his wife who was tending to their chickens. I started to wander along the shady path and was immediately taken by the range of gravestones, both elaborate and simple, and went to take a photo. Their delightfully serious little daughter can running up and politely informed me it was yasak, forbidden to take photos. In Istanbul the reason is usually related to security, but a cemetery is, after all, the last resting place of people who once lived and breathed. Many have living relatives who grieve their loss to this day and I respect that.

The Ferikoy Protestant Cemetery is called the Feriköy Protestan Mezarlığı in Turkish, although its official name is the Evangelicorum Commune Coemeterium. Before it was established on this site in 1859, protestants living in Istanbul were usually buried in the Frankish, that’s to say the European sector of the Grand Champs des Morts cemetery in Pera, extending from modern day Beyoğlu up to Taksim.

The Great Field of the Dead, as it was known in English, dated back to the 16th century and most of the non-Muslim section took up the land between Taksim and Şişli. This area was largely open countryside until 1840 when urban transformation started. The Frankish graves were directly in the path of new residential development so the powers that be decided to close the cemetery down. By 1870 part of the former graveyard had been converted into a pretty park called Les Petit-Champs. When the Pera Palace Hotel opened nearby in 1892 on what was then called Kabristan Sokak, guests were unaware it translated as Graveyard Street.

In 1857 Sultan Abdülmecit I gifted land in Feriköy to the leading Protestant embassies of the time for use as a burial ground. While the Hancreatic States and Prussia no longer exist, today the site is still managed by consuls from the original recipients, being the UK, US, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, Hungary and Switzerland.

Approximately 5,000 individuals have been interred in the Ferikoy Protestant Cemetery since its inception. Old tombstones brought over from the Great Field of the Dead line the interior of the enclosure’s stone walls, some dating back as far as 1647. They are inscribed in assorted languages, many in English and Latin. As I strolled through the well-laid out paths I saw people had died from the plague, cholera, drowning and other ailments and accidents. Graves are grouped according to nationality, with German, Swiss, Norwegians, Dutch and others lying in neat rows. There are Italians next to Greeks next to Turks, French and Albanians. There are too many to include them all, so I’ll just share the random things I noticed.

According to the information engraved on their tombstones a number of the English residents interred in the cemetery lived and died in Haskeui, modern day Haskoy on the shores of the Golden Horn. I was surprised because I’d previously thought the population was only Turkish, Jewish, or Greek.

Franz Carl Bomonti of Bomonti beer fame is buried here. He lived from 8.6.1857 to 24.6.1903 and at the age of 15 he moved to Plovdiv with his family. Now part of modern day Bulgaria, back then Plovdiv was in the Ottoman Empire. The city had a high number of beer drinkers and the family set up a brewery which became so popular they opened a second one in Istanbul. Franz Carl joined the family business, setting up a modern industrial brewery in a neighbourhood of Istanbul now known as Bomonti as well as numerous beer gardens throughout the city. Although Franz Carl died aged only 46 and Anadolu Efes took over the business in the 1930s, Bomonti beer is still available in Istanbul. To learn more about the family’s history click here.

Then there’s the Barnums. Not of circus fame, but missionaries. Helen Randle Barnum, married to Henry Samuel Barnum was buried here on 31 January 1914 as was her son. Henry Huntington Barnum, a maths professor, died on 28 June 1939.

Of note is the Schlerff family tomb. In 1860 a German named Schlerff (I haven’t been able to work out his first name) became head palace gardener, and worked on the grounds of Yildiz Palace. A postcard dating from 1903 refers to the Istanbul Villa Schlerff in Maslak, where presumably he lived at some stage.

The most recent grave I came across in the Ferikoy Protestant Cemetery was that of famous but controversial historian and author Norman Stone. Born on 8.3.1941, Stone died on 19.6.2019. He was professor of European History at Bilkent University, a professor at the University of Oxford and lecturer at the University of Cambridge and also an adviser to British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

Interestingly, the graves of Armenian Protestants are separate from the area containing the graves of foreign Protestants. This is because Armenians were categorised as Ottoman subjects. They lie alongside Greeks, Arabs, Assyrians and Turkish Protestants, the majority of whom converted from Islam. Epitaphs are written in five different languages.

*************************

After an embarrassing number of long treks to the tekel I realised I could shorten my walk by cutting through a narrow street parallel to the larger of the two walled enclosures. Each time I did so I noticed a nondescript doorway with the words Latin Katolik Kabristani on the archway but thought nothing of it so decided not to stop. I usually do my wine run at the end of a day’s research based sightseeing which means I’m pretty tired by the time I get there. Consequently it took me even longer to visit the Feriköy Catholic Cemetery in the larger walled enclosure across the road from the Ferikoy Protestant Cemetery.

When I finally walked through the door, I saw a much larger space than over the way. As with the Protestant Cemetery no photos are allowed so I ask that if you do go there, please respect this. I do not support bucket-list type tourism at the expense of local traditions and basic decency. Visits like these are aimed at reminding us of Istanbul’s rich, complex history, multicultural past and to help fill in the gaps.

As is my wont I wandered aimlessly. I noticed graves brought from the Grand Champs des Morts as well as a big square tomb with Latin inscriptions and a pedestrian boulevard lined with family tombs. There was a chapel dating from 1863 and then an area full of fallen Italian soldiers from Sardinia who died in the Crimean War. The Crimean War took place between 1853 and 1856 when the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and the Kingdom of Sardinia (the modern day region of Piedmont) fought against Tsar Nicholas I. A pyramid shaped memorial tomb stands in remembrance of them. In a shady spot adjacent, there are rows of Italian military graves marked by small white crosses with brass plates. Judging by the dates on them (1918-1923) they all died during occupation of Istanbul.

Another memorial remembers the Hungarian freedom fighters of 1848–1849.

In 1862 the bodies of French military personnel who died in the Crimean War were exhumed and reburied here. A memorial commemorates the 26,000 who never made it home. There’s also a section of small crosses dedicated to the French soldiers killed in World War I. There are several ossuaries, structures containing the skulls and bones of the deceased, one in the shape of a giant diving bell that looked to me like a Raimondo D’Aronco design. Another one, a large square sarcophagus, is covered with 178 tombstones previously located in the Great Field of the Dead. Inside are the remains of people originally buried at the former graveyard. This monument was completed in 1871.

The daughter of Wladimir Rudolf Karl Freiherr Giesl von Gieslingen, an Austro-Hungarian general and diplomat during the first world war is buried here. Bearing the grand name Baroness Maja Giesl von Gieslingen, little Maja spent the whole of her short life in Istanbul, born on 5 October 1900 before dying on 6 March 1905.

One memorial that has seen activity recently is the memorial to Wojciech Rychlewicz. During WWII he was Chief of Mission for the Consulate General of the Republic of Poland. He used his position to issue certificates stating the bearer was a Catholic, to Jews trying to flee Europe and the onslaught of Adolph Hitler. Rychlewicz helped save at least 5,000 Jews while stationed in Istanbul between 1936 and 1941. He became a member of the Anders’ Army, a Polish resistance movement against the Nazis, in Palestine in 1942. Afterwards he retired from his commission and moved to London in 1946, where he died on 8 December 1964. The Polish President Andrzej Sebastian Duda inaugurated the monument on May 27, 2021.

I hope you enjoyed visiting the graveyard with me. To discover more have a look at Istanbul Cemeteries and Turkish Symbolism. If you’d like to see pictures of some of the graves you can do so via this link) and through the Visitors Guide.

*************************

Planning to come to Istanbul or Turkey? Here are my helpful tips for planning your trip.

For FLIGHTS I like to use Kiwi.com.

Don’t pay extra for an E-VISA. Here’s my post on everything to know before you take off.

However E-SIM are the way to go to stay connected with a local phone number and mobile data on the go. Airalo is easy to use and affordable.

Even if I never claim on it, I always take out TRAVEL INSURANCE. I recommend Visitors Coverage.

I’m a big advocate of public transport, but know it’s not suitable for everyone all the time. When I need to be picked up from or get to Istanbul Airport or Sabiha Gokcen Airport, I use one of these GetYourGuide website AIRPORT TRANSFERS.

ACCOMMODATION: When I want to find a place to stay I use Booking.com.

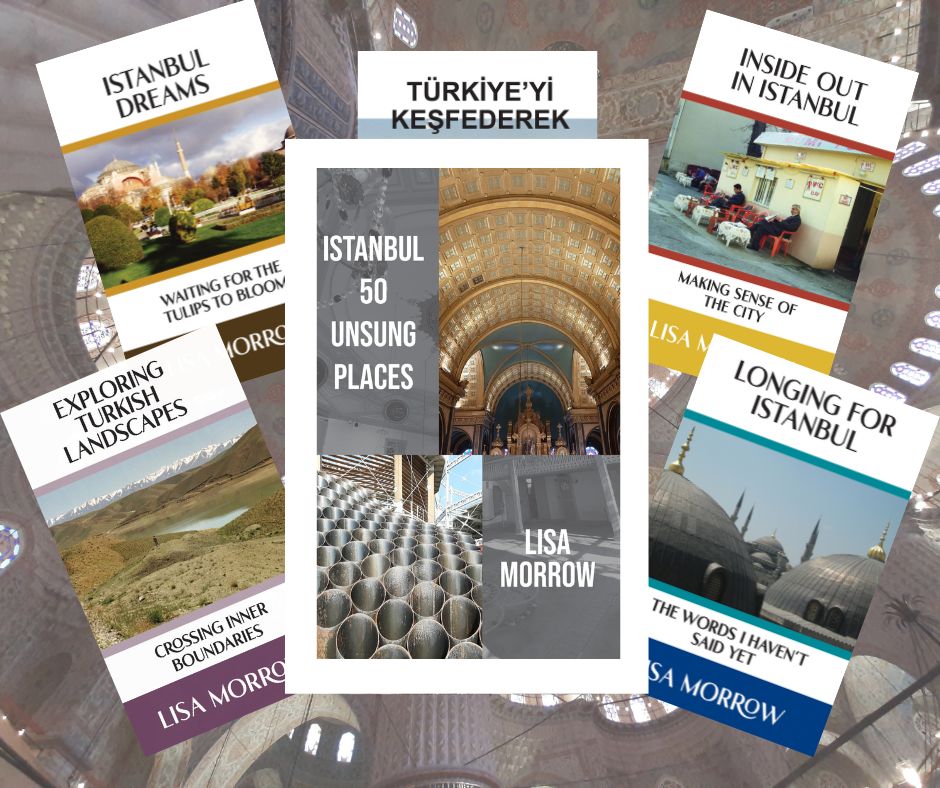

CITY TOURS & DAY TRIPS: Let me guide you around Kadikoy with my audio walking tour Stepping back through Chalcedon or venture further afield with my bespoke guidebook Istanbul 50 Unsung Places. I know you’ll love visiting the lesser-known sites I’ve included. It’s based on using public transport as much as possible so you won’t be adding too much to your carbon footprint. Then read about what you’ve seen and experienced in my three essay collections and memoir about moving to Istanbul permanently.

Browse the GetYourGuide website or Viator to find even more ways to experience Istanbul and Turkey with food tours, visits to the old city, evening Bosphorus cruises and more!

However you travel, stay safe and have fun! Iyi yolculuklar.

Loved this Lisa

and I’m afraid Scherff perked my interest and I did a little search – info about him with links (all in German). I’m intrigued by the fact he served all of the Sultans below.

(Johann) Adam Schlerff (1834 – 1907) born in Sachsenhausen or Dreieichenhain (the latter lays claim to him on Wikipedia https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dreieichenhain) Frankfurt am Main, entered into service as a foreman in 1857 in Constantinople, and became the Sultan’s head gardener. In his time he served under Abdülmecid I. (1839–1861), Abdul Aziz (1861–1876), Murad V. (1876) und Abdul Hamid II. (1876–1909) and developed 16 new gardens for the Sultans. Died (Constantinople) 12.1.1907. His death gets a brief mention on the City Chronicle for Frankfurt https://www.stadtgeschichte-ffm.de/de/stadtgeschichte/stadtchronik/1907.

Thanks for this Rosie. I delved more into Scherff when I was doing research for this piece and realised he’s worthy of a whole post if not a book on his own. Maybe a project for you, given your knowledge of German?

What an interesting read thank you .

Put that on the list for a visit.

I’m glad you enjoyed it and will enjoy the cemetery when you see it, if you know what I mean!

Interesting information, thanks Lisa. As Helen says, the links are great too. I met Norman Stone in Istanbul a couple of years before he died, when he lived in Galata, but had no idea he was so controversial!

I’m glad you liked it. I had no idea about Norman Stone either until I started to research him for this post. I imagine he was much nicer in person. At least I hope so.

Yes! He was very charming with a twinkle in his eye (and a fabulous balcony with Bosphorus views).

Really interesting post – thank you. I enjoy your writing. The links are good, too. Impressed by Barbara Dobbins’ research on the Americans buried in the cemetery. Feel so sorry for the woman who ‘died on the train from Ankara’, and what about bad boy Gary Ralph Bouldin?

Glad you liked it and yes, there are so many stories contained within its walls.