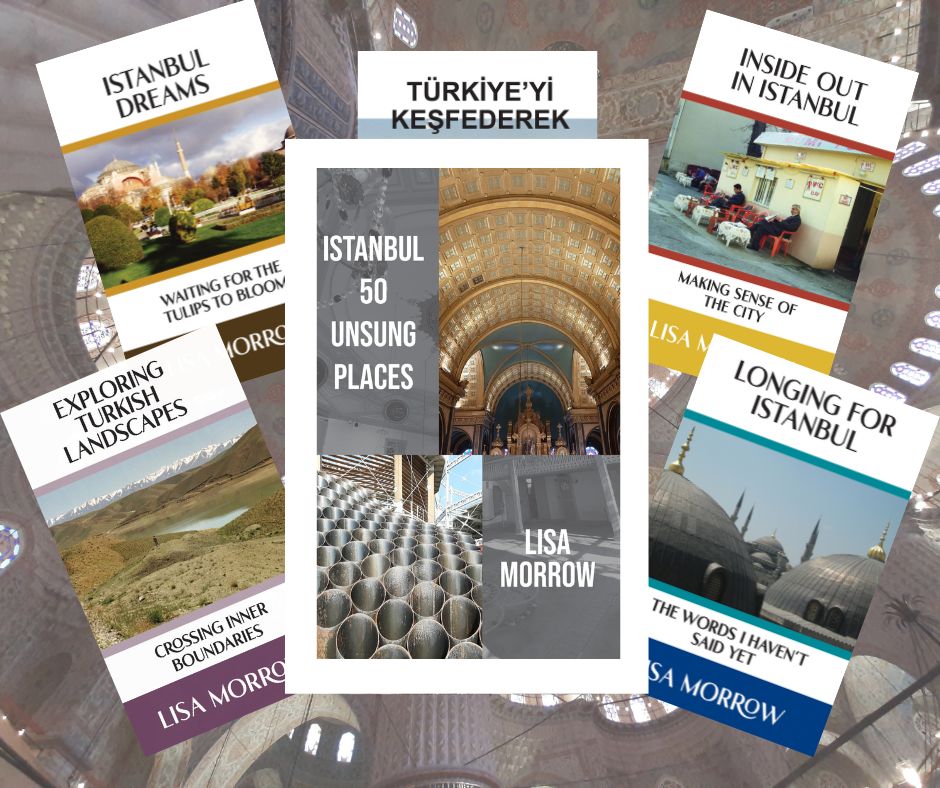

The Hagia Sophia in Istanbul and Thomas Whittemore

Reams have been written about the Hagia Sophia, originally a Byzantine church, mosque, museum and now a mosque again, so I thought it was high time I wrote a post about it for Inside Out In Istanbul. The inspiration for this came not from a visit to the building itself, but from an exhibition of water colours by Alexis Gritchenko put on by Meşher Gallery a few years ago. Gritchenko was a Ukrainian who spent time in Istanbul when it was occupied by the Allies after World War One. As well as a display of wonderfully evocative paintings, there was a small section dedicated to the work of a man called Thomas Whittemore. Whittemore bought 66 paintings, since lost, off Gritchenko back in the 1930s, but more on the former later. Let’s start with the essentials.

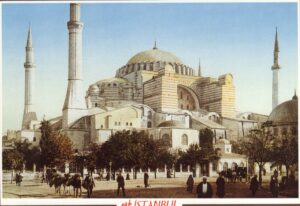

The Hagia Sophia is located on the first of Istanbul’s seven hills, on the historic peninsula surrounded by water on three sides. The first church built where the Hagia Sophia now stands was for Emperor Konstantios in 360 AD. A much simpler structure, it had a wooden roof and was called Megale Ekklesia, meaning the Big Church. The Archbishop of Constantinople at the time was Ioannes Hrisostosmos (John Chrysostom), an aesthetic who spoke out against financial abuse by the authorities and lavish displays of wealth. A speech he made in 404 about women’s extravagant garments brought him to the attention of Eudoksia, the wife of Emperor Arkadios. She thought his remarks were aimed at her so sent him into exile. The local populace, big fans of the archbishop, rose up in protest and in the ensuing chaos a fire destroyed the church. A second church built on the orders of Theodosius II was inaugurated on 415 but it too was destroyed, in the Nika riots of 532.

Work on the present day Hagia Sophia began that same year on the orders of Emperor Justinian I. The emperor wanted to celebrate his victory over his opponents by constructing the grandest church ever seen in Constantinople, the then capital of the Roman Empire. He appointed mathematician Anthemios of Tralles (modern-day Aydin), as head architect assisted by Isidorus of Miletis (today’s Balat), a scientist and mathematician, to come up with a design and complete the project. Construction took five years and the church of Holy Wisdom, as it became known, was dedicated by Justinian on December 26 in 537.

The aim was to create a structure that mirrored heaven and earth, earth represented by the ground floor with elaborate mosaics in the galleries creating the celestial world. Today a majestic dome around 31 metres in diameter hovers some 55 metres above the floor but the original dome was lower. Some years after the church opened an earthquake caused considerable damage to the eastern side of the structure, including the dome. The height of the dome was increased during rebuilding. In the following centuries further earthquakes caused more damage and the building appeared to be on the verge of collapse. As a result the huge buttresses visible today were added in 1317 by Emperor Andronicus Palaeologus.

The dome is supported by eight columns. There are 40 columns in total on the ground floor and 64 in the upper gallery. These and other columns are purported to have been brought over from Egypt and elsewhere, but it’s more likely they were created especially for the Hagia Sophia. Justinian ordered only the best white marble from Marmara Island, pink from Afyon, green porphyry from Euboea Island in Greece and yellow marble from Africa. The gallery was decorated by artisans brought in from all over the empire. They created glorious mosaics made from expensive materials such as gold and silver, interwoven with colourful stones.

After the Conquest of Istanbul

When Fatih Sultan Mehmet rode into town in 1432 he converted the church into an imperial mosque. A later sultan, Murad III, ordered the flying buttresses on either side of the structure be reinforced and tasked Mimar Sinan, arguably the greatest designer of Islamic architecture in the Ottoman Empire, with the job. It was a good call as despite numerous earthquakes over the centuries, the building has remained intact. As new sultans came to power, more additions were made and auxiliary buildings erected converting a freestanding church into a mosque complex. The final result is a grand building with a Byzantine church layout of central nave, apse and narthex, with a mihrab and minbar inside, 60-metre-high minarets built onto the exterior and a şardıvan (an ablutions fountain), medrese, library and imaret, a soup kitchen, in the grounds.

In Islam as with Orthodox Christianity, the ceiling of a holy building, in this case the dome, represents the heavens. In a mosque this space is the manifestation of the oneness with Allah, and so verses from the Koran about the sky, sun, stars and light were added to the interior of the Hagia Sophia. The most well-known one was created by Kazasker Mustafa Izzet Efendi, a calligrapher during the reign of Sultan Abdülmecid. It reads, “Allah is the Light of the heavens and the earth. His light is like a niche in which there is a lamp, the lamp is in a crystal, the crystal is like a shining star …”

Use of light in the Hagia Sophia

Light is of major importance in the design of the Hagia Sophia and the original architects paid close attention to both natural and artificial illumination in the design. Interior light was necessary from a practical perspective, but it also had a symbolic and spiritual purpose. Christians believe Christ is the incarnation of divine light and as for Muslims, light in the church represents the presence of their god. To ensure he would be ever present, the layout of the interior was determined by the position of the sun throughout the year. For example, the nave was placed so it is flooded with light at sunrise on the winter solstice. Liturgies and church services held throughout the year would be performed in different parts of the church to ensure they were illuminated. It was even possible to plan services so a ray of light would hit the alter or icons at a specific, predetermined time.

Natural light was enhanced by the use of lamps fuelled with olive oil, both single glass or lights suspended from a triangle composed of three chains. In Orthodox churches the latter are known as polykandelon while Muslims know them as mosque lamps. In addition to the light they produced, lamps were made from silver, silver-gilt and brass, materials that provided further illumination by catching the light and refracting it outwards. Individual lamps were cast in different shapes including dolphins, shops, peacocks and crosses. Many were inscribed with the name of the donor or spiritual messages. A huge polykandelon was suspended inside the main dome itself, much like mosque chandeliers today, and the brackets were fashioned in the shape of birds and human hands. It took 80 brackets to hold it in place, and many are still visible, protruding from the walls. In addition lamps were hung at different heights creating the illusion of movement, and at times the polkandelon did move, swinging slowly side to side. Salt was added to the olive oil in the lamps to prevent it from splattering. Hundreds of lamps glowed around the nave and in the 6th century silver disks were attached to the polykandelon chains, further adding to the brilliance of this artificial night sky.

All of this was pretty expensive to maintain. The lamps had to be refilled and cleaned frequently, sometimes every day. The church put money earned from over a thousand shops towards the upkeep as well as donations made by emperors.

Mosaics in the Hagia Sophia

Back in the time of Justinian, the walls on the ground floor, the main dome, semi-domes, vaults, aisles as well as the galleries of the Hagia Sophia were all covered in glittering gold mosaics. These were non-figurative. Instead they picked out geometric shapes and bands of colour and many are still in situ. The figurative mosaics date to the 9th and 10th centuries, such as the image of Leon VI over the Imperial Door. Step through into the main space and you see that each of the four pendentives at the base of the large dome features a six-winged seraphim or cherubim, their faces peering down at visitors. Another famous figurative work is one showing the Mother of God holding the baby Jesus in her lap dating to around the 10th century. There are many other mosaics, particularly in the gallery, and you’ll find the best descriptions in the book Strolling through Istanbul by Hilary Sumner-Boyd and John Freely.

Thomas Whittemore and the Hagia Sophia

Many of the mosaics in the Hagia Sophia were covered over with whitewash and not rediscovered until the early 1930s by American Thomas Whittemore. Born in 1871, Whittemore enrolled at Tufts University and after graduating with a degree in English Literature in 1894, became an academic in the university’s English Department. At the same time he enrolled in the Graduate School of Arts and Science at Harvard University, studying Fine Arts. He spent the first two decades of the new century participating in archaeological digs and assisting with post war efforts to aide Europeans displaced by World War One. He spent extended periods of time in Istanbul, initially helping Russians temporarily residing in Istanbul after fleeing the Bolshevik Revolution. In 1929 he hosted a dinner for friends at which the idea of an organisation to study, restore and conserve Byzantine art and architecture was discussed. That was to become the Byzantine Institute of America, founded in 1930.

A man of many talents, Whittemore is best known as the history buff and highly experienced archaeologist with no formal qualifications who spent 18 years painstaking overseeing the restoration of the mosaics in the Hagia Sophia. When he saw them in 1930 they were in a bad way. Somehow, to this day no one really knows how, this English Literature graduate managed to convince Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the founder of the modern Turkish Republic, to allow him to set up a team of international fieldworkers to restore and conserve the mosaics. The next year, 1931, work on the Hagia Sophia began, overseen by Whittemore, continuing even after the church was converted into a museum in 1935. He also worked on the mosaics at the Church of St Chora.

Today

Since that time hundreds of thousands of people have entered this magnificent building, inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1985. However in 2020, on July 24 (by coincidence my birthday), the Hagia Sophia opened its doors as a mosque again, a function it last performed 86 years previously. On my most recent visit, being inside the renamed Ayasofya-i Kebir Cami-i Şerifi was as moving as ever, but I was distressed seeing so many visitors taking selfies simply to prove their own existence or to mark their religious pilgrimage, clearly oblivious to the historical significance of the structure and objects within it and their meanings.

Like the two huge urns made from solid marble dating from the Hellenistic Period (330-30 BC), brought to the Hagia Sophia from the ancient city of Pergamon (Bergama) during the reign of Sultan Murad III (1574-1595). On holy nights and during religious bayram they were used to distribute sherbet to those attending prayers. Each urn can hold approximately 1250 litres of liquid. On ordinary days they contained water which people could help themselves to from taps affixed near the base. Learn more about them and other interesting features of the Hagia Sophia with a guided tour available through Viator.

Fortunately the mosaics are still in place, although at times covered by curtains. Alarmingly the walls and ceiling are showing signs of moisture damage, due I believe to higher than recommended levels of condensation forming as a result of too many bodies allowed entry at the same time. I can only hope the authorities take note and act before any permanent damage is done. Nonetheless I’m confident when you see the Hagia Sophia you’ll enjoy it as much as I did.

2024 Update

As of March 2024 non-Muslims can are no longer allowed into the ground floor of the Hagia Sophia mosque. They enter through the rear of the building and have access to the galleries which allows close up views of the mosaics and the interior. The entry price is €25, paid in local currency quivalent.

********************

Here are my helpful tips for planning your trip to Turkey

For FLIGHTS I like to use Kiwi.com.

Don’t pay extra for an E-VISA. Here’s my post on everything to know before you take off.

However E-SIM are the way to go to stay connected with a local phone number and mobile data on the go. Airalo is easy to use and affordable.

Even if I never claim on it, I always take out TRAVEL INSURANCE. I recommend Visitors Coverage.

I’m a big advocate of public transport, but know it’s not suitable for everyone all the time. When I need to be picked up from or get to Istanbul Airport or Sabiha Gokcen Airport, I use one of these GetYourGuide website AIRPORT TRANSFERS.

ACCOMMODATION: When I want to find a place to stay I use Booking.com.

CITY TOURS & DAY TRIPS: Let me guide you around Kadikoy with my audio walking tour Stepping back through Chalcedon or venture further afield with my bespoke guidebook Istanbul 50 Unsung Places. I know you’ll love visiting the lesser-known sites I’ve included. It’s based on using public transport as much as possible so you won’t be adding too much to your carbon footprint. Then read about what you’ve seen and experienced in my three essay collections and memoir about moving to Istanbul permanently.

Browse the GetYourGuide website or Viator to find even more ways to experience Istanbul and Turkey with food tours, visits to the old city, evening Bosphorus cruises and more!

However you travel, stay safe and have fun! Iyi yolculuklar.

A very interesting read, thank you. We certainly hope to visit next month just to see what we are not now able to see! Those wonderful mosaics in the gallery which, fortunately, we have captured. Sad to read about the moisture damage but I’m sure you are right.

It is definitely worth the visit as is Sultanahmet Camii, now the restoration work has been finished. Looking forward to meeting up.

Thank you for the interesting information. I visited the Hagia Sophia in 2015 and was really in awe of this beautiful place that had so much history. I spent a whole day there. Last year (2022) we visited it again and I was very disappointed. Even though we wore headscarves, we had to stand at a distance behind an iron trellis, at the edge of the main space. Most of the other people were allowed to walk around freely. It was sad that the mosaics were covered by curtains and that we weren’t allowed to go to the gallery. I also really dislike the green carpet. I understand why it is there, but the floor was much more interesting. I don’t know if I will visit it again.

It is a wonderful place to visit but I think when you’ve seen it before when it was possible to walk in the galleries and see the mosaics up close, the current visiting conditions are less than satisfactory.