Halet Cambel

Turkey’s first female Olympic competitor, archaeologist and patriot

Halet Cambel (Çambel in Turkish) was the first female Turkish athlete ever to compete in the Olympic Games. This remarkable woman represented Turkey in fencing, helped decipher Hittite hieroglyphics and founded Turkey’s first open-air museum.

Halet Cambel was born in Berlin in 1916. Her father Ibrahim Hakkı Paşa was a military attache there while her mother, Remziye Hanım, was the daughter of Hasan Cemil Çambel, a former Grand Vizier and Turkish ambassador to Germany. Halet’s father was an associate of Atatürk, who founded of the modern Turkish Republic in 1923. The Çambel family returned to Turkey the following year and Halet completed her schooling at Arnavutköy American College for Girls in Istanbul, graduating in 1935. From there she moved to Paris, and began her studies in archaeology at the Sorbonne University.

Halet Cambel the sportsperson

Heeding Atatürk’s call for Turkish women to participate in sports, Halet took up fencing at school and also mastered horse riding. She went on to represent Turkey in fencing at the 1936 Olympics held in Berlin. She was present in the stadium when American Jesse Owen enraged Hitler by winning the 100-metre sprint. Halet didn’t win any medals but made her presence felt by turning down and an invitation to meet the Fuhrer in private.

After the games she finished her undergraduate training and married Nail Çakırhan, at the time a Communist poet, in 1940. Her intention was to return to France to complete her doctoral studies, but World War II got in the way so she eventually received it from Istanbul University.

Halet Cambel the archaeologist

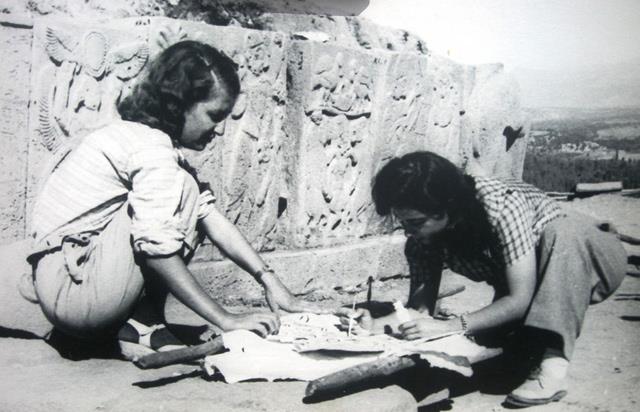

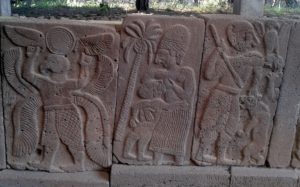

By 1946 Halet Cambel had participated in numerous archaeological digs in Anatolia with a German professor of archaeology at Istanbul University named Helmuth Bossert. Halet is best known for her work and discoveries during the Karatepe-Aslantaş excavations in 1947-1951. Together with Bossert, she travelled by horseback, following little-known trails criss-crossing the Taurus Mountains in southern Turkey. They discovered a previously unknown Hittite fortress at Karatepe and Halet successfully deciphered the hieroglyphics on a tablet covered in the Phoenecian alphabet found there. Her work allowed philologists to understand the language and read the inscription.

In the early 1950s Halet Cambel challenged the government’s plan to move artefacts from Karatepe to a museum. Passionate that the objects found on the site should remain in situ, she was instrumental in having the area overlooking the Ceyhan River declared the Karatepe-Aslantaş National Park, Turley’s first open air museum, in 1957. She took up the cause again some years later when the government wanted to dam the river.

Arguing against such a move due to the damage it would cause to many archaeological sites, she was successful in having the water level in the reservoir reduced, saving the sites. She was even successful in convincing local mountain villagers to change their livelihood.

Traditionally they grazed goats that destroyed the pine forests. Halet suggested they graze sheep instead and although the locals vehemently resisted the idea at first, in the end they thanked her as the sheep made less noise at night, improving the quality of their sleep. They were far more open to the idea of using natural dyes in the production of woollen carpets and kilims. Not only did artificial dyes fade more quickly resulting in lower quality products, natural dye carpets fetched higher prices.

Halet Cambel the academic

Not one to rest on her laurels, in 1960 Halet founded the Department of Prehistory at Istanbul University, and became chair of the department. Other than a brief period lecturing in Germany, she remained in this position until her retirement in 1984.

Halet lived in Istanbul with her husband, Nail Çakırhan, by this stage an award winning architect, in the historic Red Mansion in Arnavutköy on the shores of the Bosphorus. The mansion was designed and built by the Balyans, an Armenian family of architects. It has been fully restored and will function as a research centre dedicated to Çambel’s and Çakırhan’s work, containing personal documents and archaeological archives such as plans, drawings, and photographs from their Karatepe excavations. Classification, cataloguing and digitization efforts of this archive are ongoing. The building is best viewed on a cruise along the Bosphorus.

After 70 years of marriage her husband died in 2008. Halet Cambel lived until 2014, dying aged 97. Truly a life well lived.

********************************

Planning to come to Istanbul or Turkey? Here are my helpful tips for planning your trip

For FLIGHTS I like to use Kiwi.com.

Don’t pay extra for an E-VISA. Here’s my post on everything to know before you take off.

However E-SIM are the way to go to stay connected with a local phone number and mobile data on the go. Airalo is easy to use and affordable.

Even if I never claim on it, I always take out TRAVEL INSURANCE. I recommend Visitors Coverage.

If you’re TRAVELLING ALONE, check out this post on useful solo travel tips Turkey for women (and men).

I’m a big advocate of public transport, but know it’s not suitable for everyone all the time. When I need to be picked up from or get to Istanbul Airport or Sabiha Gokcen Airport, I use one of these GetYourGuide AIRPORT TRANSFERS.

ACCOMMODATION: When I want to find a place to stay I use Booking.com.

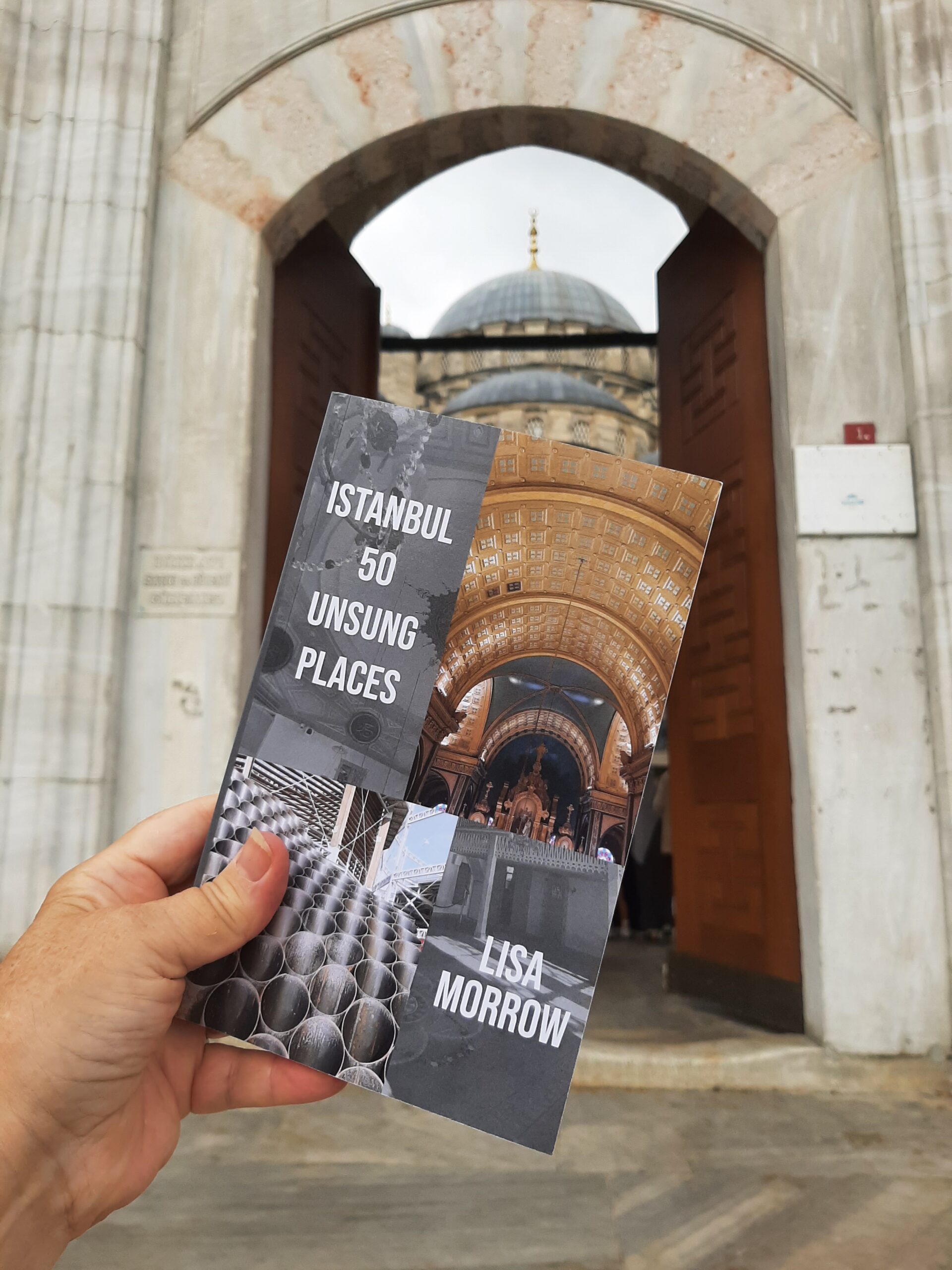

CITY TOURS & DAY TRIPS: Let me guide you around Kadikoy with my audio walking tour Stepping back through Chalcedon or venture further afield with my bespoke guidebook Istanbul 50 Unsung Places. I know you’ll love visiting the lesser-known sites I’ve included. It’s based on using public transport as much as possible so you won’t be adding too much to your carbon footprint. Then read about what you’ve seen and experienced in my three essay collections and memoir about moving to Istanbul permanently.

Browse the GetYourGuide website or Viator to find even more ways to experience Istanbul and Turkey with food tours, visits to the old city, evening Bosphorus cruises and more!

However you travel, STAY SAFE and have fun! Iyi yolculuklar.