Istanbul Cemeteries

I’ve long appreciated cemeteries. As a teenager I spent a lot of time pondering over the lives of the many people buried in the Gore Hill Cemetery in St Leonards, Sydney, where I grew up. Even aged 14 I thought it ironic that rooms in the adjacent hospital overlooked the graves. Gore Hill was established in May 1868 by William Tunks who’s buried there. He also has a park named after him, where I went the one and only time I every wagged school (and was caught out) but that’s another story.

I’ve written elsewhere about my love of cemeteries but one thing I particularly like about Istanbul cemeteries is that in this oftentimes chaotic city of 20 million people, they provide quiet green spaces away from the noise of the traffic and the urgent tide of humanity. Unless of course it’s Ramazan Bayramı. This time to reflect on absent relatives sees dozens of families visit their loved ones in Istanbul cemeteries and others all over the country.

I find the way Turks deal with death very different from in my own culture. When my dad died*, not being religious, there were no rituals to carry out that helped get me through the funeral. I just had to grit my teeth and get on with it. When a person dies in Turkey, Islamic cultural practices mean that regardless of the particular religious depth of the person in question, certain steps are followed. Muslims believe in an afterlife so people are buried, not cremated. The funeral usually takes place within 48 hours of death, and they are buried with their heads facing Mecca.

These days headstones in Istanbul cemeteries are quite plain, even the large ones set in family tombs, especially when compared to headstones from the Ottoman period. Back then, they functioned as biographies of the deceased. The statement that Allah is the only creator usually appears at the top, then verses from the Koran and hadiths (sayings attributed to the Prophet Muhammed) are carved underneath, followed by the name of the deceased and their date of death, along with advice and requests for blessings and prayers. Each symbol on the gravestones, the designs they incorporated and even the trees planted around them all have meanings, as I wrote about in this post on Turkish symbolism.

Compared to where I come from, you find cemeteries and tombs in the strangest places in Istanbul. That’s because the Ottomans liked to keep the departed near to them, often in the middle (literally) of ordinary streets, behind mosques or next to hamam and halls. Muslim cemeteries aren’t hidden by walls to remind us that life is ephemeral and we should make the most of the short time we have. Passersby still often stop and say a prayer for the dead, even if they’re long gone and not kin.

The grand mausoleum belonging to Sultan Mahmut II on Divan Yolu in Sultanahmet is one of the Istanbul cemeteries most visitors to the city will have seen, if not actually been inside. Sultan Abdülmecit commissioned it in 1839 just after he ascended the throne, for his late father Sultan Mahmut II. It was designed by Armenian Ottoman architect brothers, Ohannes Dadyan and Bogos Dadyan and inaugurated on 11 November, 1840. Mahmut II was famous as a champion of Western innovations and wanted to modernise Turkey, and the complex is a testament of this. A globe on the outdoor fountain represented the revolution of science and rationalism happening Europe in that period. A crystal chandelier hangs inside the octagonal shaped mausoleum, a present from Queen Victoria. The gilded clocks sitting on either side of the entrance were gifted by French Emperor Napoleon III. Although dedicated to Mahmut II, it was common practice to bury successive sultans in the same mausoleum. Consequently it also contains two other cists (stone burial chambers) containing his son Sultan Abdülaziz and his grandson Sultan Abdülhamit II.

The garden surrounding the mausoleum became a cemetery in 1861 and around 150 people were buried here, including authors, poets and members of the Ottoman elite. Unequal in life, in death revolutionaries lie side-by-side with pious leaders and conservative Ottoman statesmen. It’s worth making the time to inspect the gravestones to get an idea of the artistry involved, such as on the tomb of Sadullah Paşa. He was the Ottoman ambassador in Vienna, and his headstone is carved with a globe, plumes and a book to indicate he was an educated man. Another grave of note is that of Osman Ertuğrul Efendi. He was the last ever Ottoman şehzade, a prince. He was born in the Ottoman Palace, died in New York as an exile and was buried here in 2009.

As well as individual tomb complexes there are large Istanbul cemeteries like Karaacaahmet in Uksudar (where you can see the fabulous Şakırın Camii) and the large multifaith cemeteries surrounding the Balıklı Meryem Ana Rum Ortodoks Manastırı (you’ll find more details about the monastery and how to get there in my guidebook Istanbul 50 Unsung Places) in Zeytinburnu. Then there are numerous smaller ones all over the city, where you’ll find some exceptional individuals buried in unassuming out of the way places.

A short seven minute walk from Fıstıkağaç metro stop brings you to the Sultanepe Mezarlığı next to Özbekler Tekkesi, a Mevlevi Sufi lodge. It’s one of many small Istanbul cemeteries but right next to the pavement you’ll see a plain white marble stone etched in Turkish. It commemorates the life and history of Sudenli Zenci+ Musa Bey, a Sudanese man born a free man in Crete in 1880 who lived a short but extraordinary life. After his dad died Musa Bey moved to Cairo with his grandfather where he learned Turkish, then fought the Italians in Tunisia and Libya in 1911 alongside his granddad, became a member of the Ottoman intelligence service, was a volunteer soldier in the Ottoman army during the Balkan Wars and WWI, and the body guard and personal orderly of famous Ottoman intelligence officer Kuşçubaşı Eşref(1883–1964).

Musa played his part during the Turkish War of Independence basically as a secret agent. By day he was a hamal, a porter, but at night he helped the underground organisations smuggling arms and ammunition from Istanbul into Anatolia.

He was living at the tekke when he died from tuberculosis aged 39 in 1919. The exact location of Sudenli Zenci Musa Bey’s grave is unknown but his bravery and devotion to his adopted country were recognised in a poem by renowned Turkish poet Mehmet Akif Ersoy, the man who wrote the lyrics for the Turkish National Anthem, after the two met during a trip to the Arabian Peninsula in 1915.

Another permanent resident of the cemetery is Ahmet Ertegün whose burial site is clearly marked. He has quite the pedigree, starting with his great-grandfather Ibrahm Edhem Efendi who was a Sufi sheikh at the lodge. Then there’s Ahmet’s dad. The street where you find the lodge is named for him, Münir Ertegun Sokak. Münir Bey was the first Turkish ambassador to the United States. While living there young Ahmet developed a taste for jazz and blues at mixed race functions held by his father, at a time when apartheid, politely called racial segregation or referred to by the racist term Jim Crow, was enshrined in law. He went on to become the cofounder of Atlantic Records. You know, the company that signed greats like Ray Charles, John Coltrane and Aretha Franklin, just to name a few.

These are just some of the stories you can glean from Istanbul cemeteries. If you share my passion, you’ll want to check out the following.

There are separate Greek Orthodox, Muslim, Armenian and Jewish Istanbul cemeteries located on either side of the highway on the sprawling hills of Çıksalın, on the north bank of the Golden Horn. Nearby you’ll find the mausoleum of Abraham Camondo, of Karaköy stairs fame. If you want to know how to get there check out the entry in Istanbul 50 Unsung Places.

My favourite out of all the Istanbul cemeteries is Haydarpaşa cemetery on the Asian side of the city. You’ll find all you need to know about it, including how to get there in my guide as well.

Last on this by no means complete list of Istanbul cemeteries is the Feriköy Protestant Cemetery in Şişli.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this short look at Istanbul cemeteries and the city’s lived history, so to speak. If cemeteries speak to you too, there are more than 560 of them dotted around the city. I’m sure you’ll come across at least one next time you go exploring. Iyi geziler!

*********************

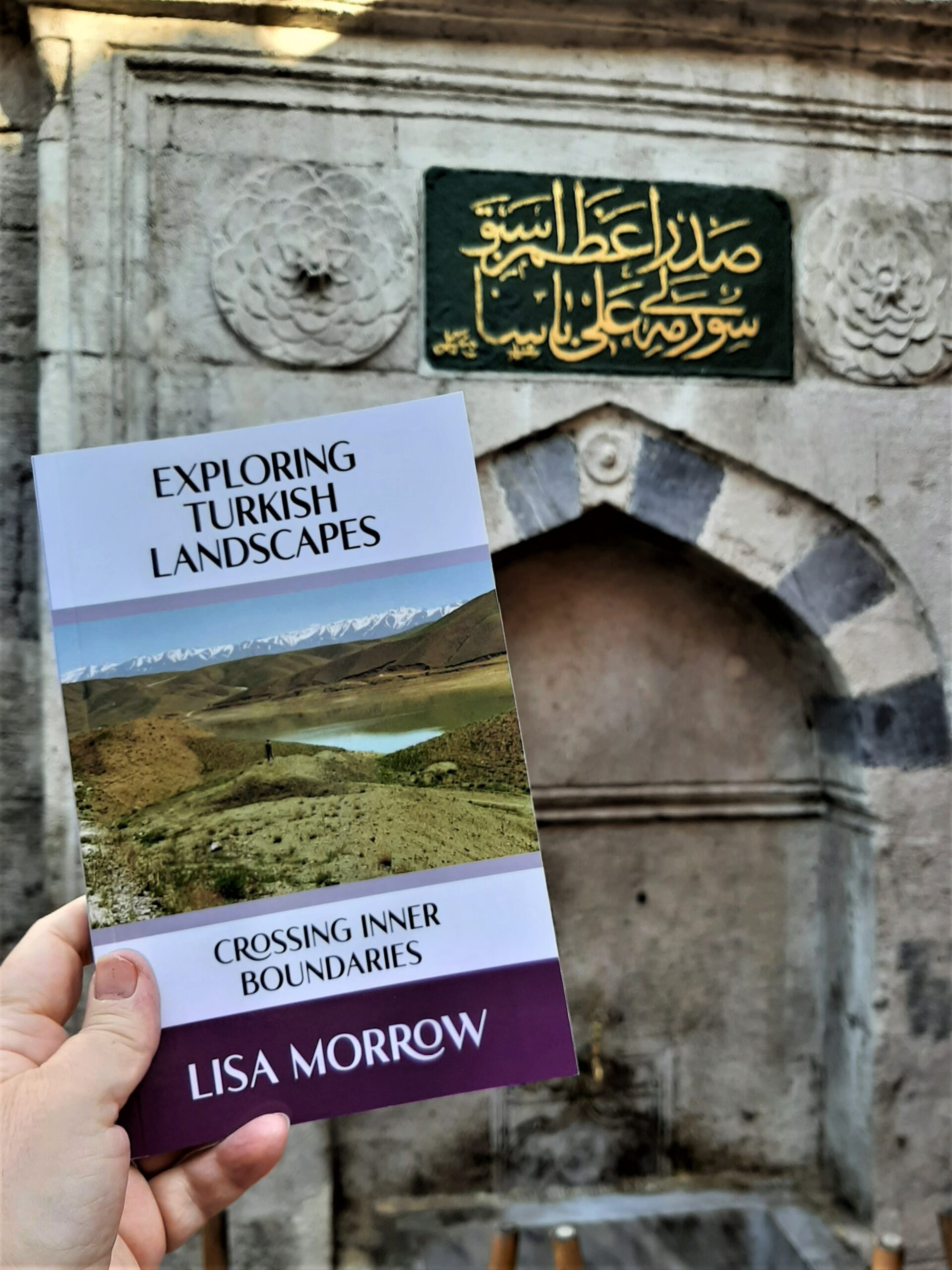

*You can read the whole story, ‘You are my sunshine’, in Exploring Turkish Landscapes: Crossing Inner Boundaries.

+ In modern spoken Turkish, the word zenci is used to refer to someone with black skin, but literally describes a person from the Zenc region of Africa. In today’s geography this region roughly corresponds to East Africa, as in Sudan, but more specifically Zanzibar. In Arabic Zanzibar was called Zencibar and the inhabitants were known as Zenci. It is now considered a racist term due to the fact the word zenic entered the Turkish language because most slaves came from Sudan and Tanzania in the Ottoman era. Even after gaining their freedom, former slaves were still referred to by the word zenci.