Ramazan – The joys of staying out late

The Muslim religious obligation to fast for a month, known as Ramazan in Turkish, is held at a different time each year. The start is determined by the lunar calendar, and the first fasting day is around eleven days earlier each year. Muslims fast to show solidarity with those who rarely have enough food to eat, and it’s particularly hard in summer when they can’t drink any water during daylight hours, no matter how thirsty they get. Those who smoke say going without a cigarette for so many hours is the worst thing of all.

The first of the two meals of the day is sahur, a type of breakfast which occurs a few hours before dawn. People have to eat enough at this meal to keep going all day. In the past it was the tradition in every village, town and city of Turkey for drummers to walk the streets, counting out a steady beat to wake those who were sleeping. Despite the advent of alarm clocks, this tradition continues in many areas of the country, including Istanbul. In the month leading up to the fasting period, auditions are held by local councils and the best drummers are chosen for the task.

A few years ago, just before Ramazan started, a notice was posted on our entryway bulletin board showing pictures of the successful team. As well as providing all their personal information, such as their names and copies of their Turkish identity cards, the notice warned residents to be careful when it’s time to pay for their services at the end of the fasting month. We were urged to compare the identity of those claiming payment carefully with their pictures, and to ask to see their identity cards, because pirate drummers sometimes masquerade as the genuine ones.

At first, my husband Kim and I thought this was really funny, and wondered who’d already be awake at 3am to peer out the window and check the faces of the people making all the noise.

The answer to that question was us. The first Friday night we got home around 2am. Just as we were drifting off to sleep around three, we were woken by the sound of drums. At first there was only a distant beat but then it got louder and we realised it was the Ramazan drummers doing their rounds. We heard them as they passed by the front of our building, and then again as they walked down the street at the back of our building. By the time the noise had subsided we were fully awake.

From that night on we decided we’d should go to bed well before midnight, but as it was summer we chose the more enjoyable option and usually stayed out well past three.

For the whole of the month, when we went out for dinner with friends, we had to wait until fairly late to get fed. Iftar, the evening meal of the period, takes place when a white thread can no longer be distinguished when it’s held up against the evening sky. In summer fasters have to mark time until at least eight o’clock before they can eat. Despite the rigours associated with the fasting month, the iftar meal is seen as a joyous occasion and the perfect opportunity to spend time with family and friends.

The meal usually starts with a bite of honey still on the comb and dates brought in from Saudi Arabia, before moving on to a series of more substantial and filling courses. Despite their hunger, people eat at a measured pace and often sit around for hours after the food has been removed, smoking cigarettes and chatting.

Not wishing to join queues of up to a hundred people waiting outside each and every restaurant, we chose to have a drink at a well-hidden bar we knew in Kadıköy before emerging a few hours later to have a meal. As foreigners we’d be forgiven if we ate before the guns announcing the end of the fast had sounded, but we choose not to.

In daylight hours we tend to eat more at home, and take care the neighbours don’t see us. Not everybody has to fast, and the young, aged and infirm are excused, but as foreigners living here permanently we try to show our respect for this tradition. Sometimes, when the heat is still fierce we don’t feel hungry early in the evening anyway, so eating late is practical.

Ramazan isn’t only a time of doing without. It’s also a time of celebration. In Sultanahmet, at the Hippodrome, which normally plays host to thousands of foreign tourists, hundreds of picnic tables are provided at which people can sit and eat. By 7pm every one of them is occupied by groups of Turks, sitting with parcels of food and non-alcoholic drinks set out in front of them, patiently waiting for the call from the mosque to signal the start of iftar. Some families bring home-cooked food while others line up at the many food stands specially set up for the month.

All the surrounding restaurants are completely booked out by large Turkish groups and tourists barely get a look in. I love seeing Sultanahmet being overtaken by ordinary Turkish people once more. It’s quite wonderful. Here and in many areas of Istanbul, huge fetes are held, featuring the best of Turkey’s traditional arts and food specialities. After eating their fill everyone strolls around until the early hours marvelling at everything on offer.

In the carnival air of the Ramazan entertainments it can be easy to forget it’s an intensely pious occasion. Every local mosque has food tents where the poor and needy can come each day for a free evening meal, and other free iftar meals are organised by neighbourhood groups and councils all over Istanbul. In the past, Muslims were supposed to enter into a kind of retreat in the mosque for the last ten days of this holy month.

Although that doesn’t happen as often now, Kadir Gecesi or the Night of Power, when the Prophet Mohammed is purported to have received the first revelation of the Koran from the Angel Gabriel, is widely commemorated. All the mosques are full until dawn, as the devout believe that on this special night their prayers will be answered.

My Ramazan nights ends with sahur shared with friends, then I go home to sleep, aware that while I may not share their religion, at times like these I am privileged to share their life.

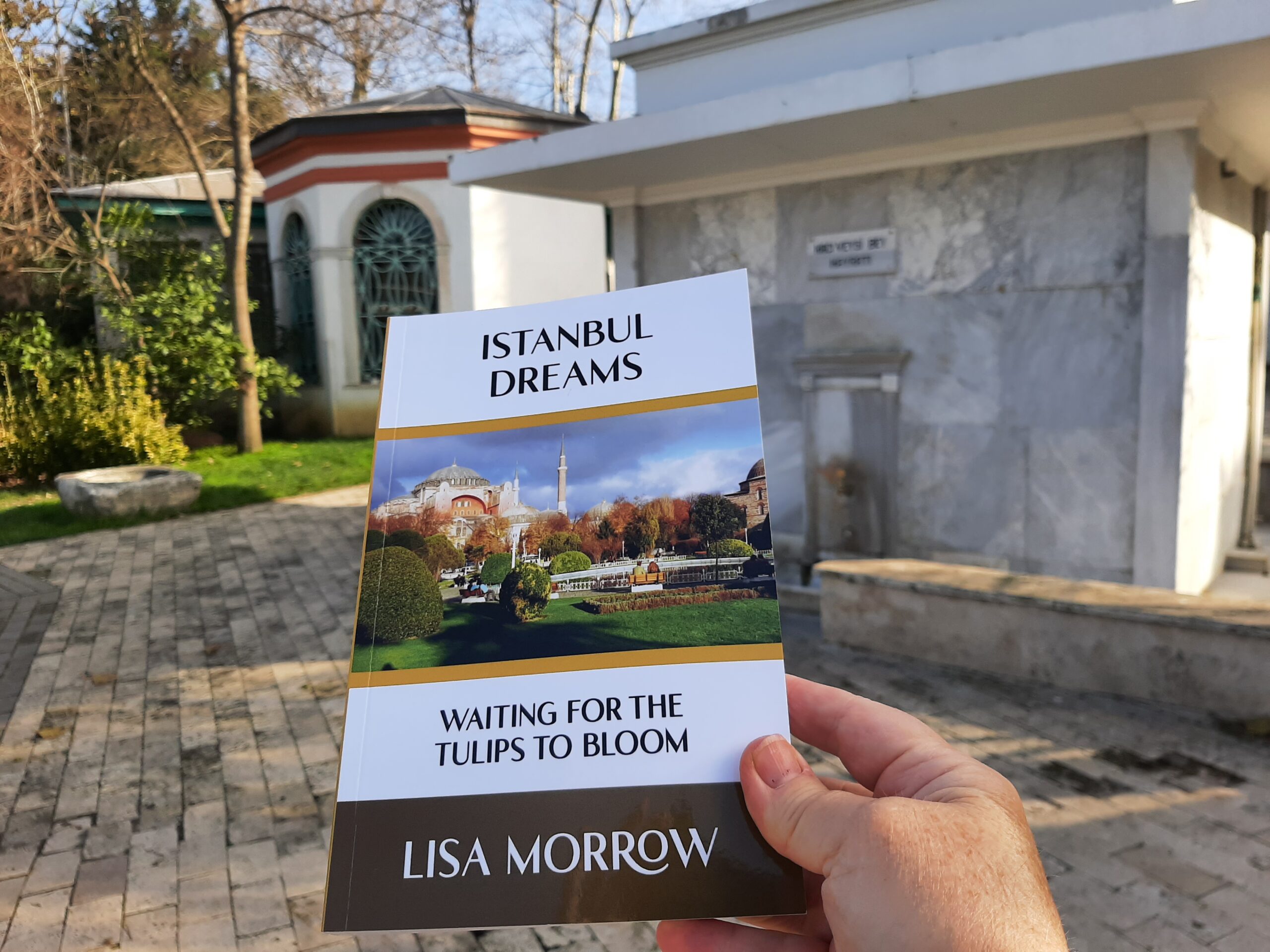

Curious to learn why I chose to call Turkey home? Read all about in my memoir

Istanbul Dreams: Waiting for the Tulips to Bloom. Iyi Ramazanlar!

I really enjoyed your post and will be buying your book very soon. 🙂 My husband and I were in Istanbul during Ramazan in September a few years ago. Besides being discreet about day time eating we found the evenings in the Hippodrome great fun. As we visit Istanbul regularly, usually end of April/beginning if May we will look forward to Ramazan again when the weather isn’t quite so hot.

Hi Judy,

Thanks very much for taking the time to comment. I hope you enjoy my book! Ramazan in Sultanahmet is a wonderful experience, isn’t it! However for people who fast, particularly in summer, it can be quite hard. At the moment that means 17 hours of not eating and even more difficult, not drinking anything. I too help by being discrete when I drink and eat in daylight hours.

Cheers,

Lisa

It’s good to be reminded of the reasons for Ramazan and its positive aspects at a time when the entire Western machinery of press and politicians is bent on demonising Islam and Muslims. I can’t remember the last time I saw anything positive about Muslims or Islam in the British press and media. Thank you for posting.

I’m glad you enjoyed my post John, as much as you enjoyed going to Sultanahmet during Ramazan when you were here a few years ago. Please feel free to share my blog with your friends.