Turkish Delight – A Mouthful of Dreams

This story comes from my book Exploring Turkish Landscapes: Crossing Inner Boundaries.

When I was at high school I studied history. Learning dates wasn’t something I was any good at and while I didn’t actually fail, it was a struggle. The facts and figures the teacher wrote on the board lacked colour and excitement and nothing ever stayed in my memory. Living in Istanbul however, it’s almost impossible not to learn about history. History is woven into everyday life and most of the things I see and do are imbued with the past so it’s easy to learn. Here the past is vibrantly alive.

One of my favourite things about Turkey is the food, especially the sweets. I have sampled them all, the milk puddings, the chocolates and the cakes, but I absolutely adore Turkish Delight. Known locally as lokum, it is a sweet made from starch, sugar and assorted flavourings. The name is derived from the Arabic rahat’ül hülküm, literally meaning ‘comfort of the throat’. I don’t buy this comfort from just any shop though. Years ago I asked my Turkish friends for their recommendations, and they all said I should go to Ali Muhiddin Hacı Bekir. I have been enjoying their lokum for years now, but I only recently took the time to research their history. Although I discovered a few romantic tales involving sultans, jealous women in the harem, and the hardworking sweet makers tasked with creating something to stop them fighting, it is widely believed the sweet we know today was invented in Turkey back in the 18th century by Mr Bekir himself.

In 1777 he came from the Araç district of Kastamonu in the Black Sea region to Istanbul. Called hacı because he had already made a pilgrimage to Mecca, Ali Muhiddin Hacı Bekir opened a small sweet shop in Bahçekapı, near the New Mosque in Eminonu, where he started making and selling lokum, the best known being the one flavoured with rose water. He also made boiled lollies and candied fruit. Due to the original nature of the sweets and the care with which they were made, Hacı Bekir won the approval of the people and the Ottoman Sultans, and was awarded the role of confectioner to the Ottoman Palace. At around the same time an Englishman visiting Istanbul so liked these ‘mouthfuls of delight’ that he took some back home with him and introduced it as Turkish Delight to his circle of friends. In the 19th century the Hacı Bekir company participated in many international fairs, introducing this very traditional Turkish sweet to the world and winning numerous gold and silver medals along the way.

There are several Hacı Bekir shops in Istanbul but I go to the one in Kadıköy, my local shopping area. When I peer into the panelled bow shaped front windows at plates of their famous Turkish Delight and their less well-known but equally wonderful badem ezme, made from ground almond meal in assorted flavours, my mouth starts to water. As I step through the wood and glass front doors into an interior I suspect has changed little since its inception in the 1930s, I start to smile.

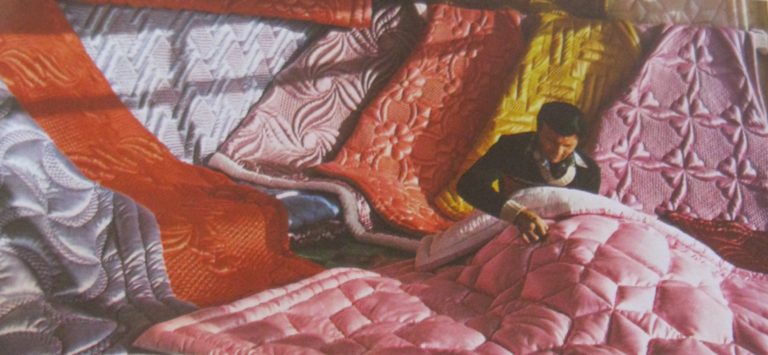

Darting around the shop is a little boy pointing excitedly at the displays, begging his parents to buy one of everything. Slowly but surely he is drawn to an old wooden cabinet full of colourful sweets. As he delightedly presses his face up against the sparklingly clean glass his parent give consideration to choosing a box for their selections. There are gift boxes neatly stacked on shelves on either side of the shop. Giving sweets as gifts, be it chocolates or Turkish Delight, has a very important role in Turkish culture and sweets accompany everything from birth through to death. Sugar almonds are still given to those viewing newborns for the first time while lokum is served on the 40th and 52nd days after a death. On the first anniversary of the loss lokum is served once again in a ceremony called a mevlit. In the shop the boy’s mother lingers over the square padded boxes covered in luxurious swathes of velvet while the father favours the more austere round wooden boxes stamped with the logo designed to celebrate the forming of the Turkish Republic.

Next to them stand an old man and his wife, patiently waiting to buy a paper twist of akide, or Turkish boiled lollies. In front of them is a row of tall glass jars, topped with conical lids made of thin sheets of brass or copper. The sweets inside them look exotic and expensive and indeed in the past boiled lollies were highly valued due to the exorbitant price of sugar, and the difficulty in making them due to its lack of consistency. Although refined sugar means the consistency is better, the process of making akide is still difficult and finicky. The faces of these customers are lined and wrinkled, yet I can see the small children they once were, as they pause and consider their choices. What flavour should they have – the rose or the cinnamon, the chocolate or the mint? It is a solemn ritual accompanied by gentle arguments and happy endings. It is obvious that for this couple the value of the akide lies as much in the memories they bring, as in the taste. The word akide also means confession of faith and the lollies were used as a pledge of loyalty in Ottoman times. The Janissary, the royal guard of the ruling sultan, was paid every three months. If they were happy with their salary they would present a gift of mouthwatering akide to the high court officials as a sign of their fidelity to the sultan. What they would do if they were unhappy is another story.

Walking across the wavy black and white tile pattern floor to the back of the shop, I am transported to an earlier, gentler era. As I sit and dreamily wait for my Turkish coffee and the two different flavours of lokum I finally decided on, I gaze at the people around me. Opposite me a woman sits alone drinking sherbet. Şerbet sekeri is also known as logusa in Turkish and is used to describe a woman who has recently given birth. Traditionally a sherbert drink was made the day after the birth for the new mother to take advantage of its health benefits. Now şerbet sekeri is better known as a refreshing summer drink, and the woman opposite is enjoying it along with two pieces of rose-petal flavour Turkish Delight. At the table next to her a couple sits in companionable silence. He sips a tea while his wife slowly spoons up ice cream from an old-fashioned soda glass. I notice she doesn’t offer him any and he doesn’t ask. At another table three women laugh and chat over a mixed plate of candied fruit, lokum and badem ezme.

The walls around us are quite plain, simply decorated with framed award certificates won at international food expositions in France at the end of the 20th century and prints of the different logos Hacı Bekir have used over time. It seems fitting that the décor of the shop remains suspended in history. What was important back in 1777 is still important today. We come for the Turkish Delight, a simple concoction of sugar, starch and flavour, for its exquisite taste and the meanings each of us associates with it. Whether we grew up in Turkey or somewhere else, one small piece of Turkish Delight fills both the mouth and the heart with dreams.

*************************************

Where to buy Turkish Delight in Istanbul and more

You can find out how to get to Haci Bekir in Kadikoy from anywhere in Istanbul in my alternative guide to the city Istanbul 50 Unsung Places, as well as 49 other off the beaten track places , all by public transport.