Turkish Films

In these days of films on demand, streaming and Bluetooth, it’s easy to forget just how important the film industry once was. It took a while for Turks to become producers and directors, but once they embraced the idea, there was no stopping them from making Turkish films.

Less than a year after the Lumier brothers showed the first ever film in a café in Paris in 1895, one Sigmund Weinburg began to screen films in a beer hall in Galatasary, Istanbul. It proved very popular so from about 1908 many minority group Istanbullu, such as Rum (Turkish born Greeks) and Armenians, began to open cinema halls. It wasn’t until 1914 that two Turks, Cevat Boyer and Murat Bey opened one. The first Turkish film, a documentary, was made by the army, and subsequent films, mainly comedies, by the War Veteran’s Association.

In 1922 Kemal Films was established, based in the Feshane building on the Golden Horn, by Kemal and Şakir Seden. Harnessing the talents of theatre actor Muhsin Ertuğrul as director, they produced a film called Ateşten Gömlek (The Ordeal), based on a novel by Halide Edip. It starred the first ever Turkish Muslim actresses, Bedia Muhavvit and Neyyire Neyir and was also the first movie to deal with the War of Independence. It was shown in Istanbul in 1923, when it was still occupied and run by the Allied forces.

Over the next two decades Muhsin Ertuğrul put Turkish cinema on the world stage, participating in the Second Venice International Film Festival in 1934. By the end of the Second World War he had been joined by many more directors and production companies, which began to organise themselves by forming professional organisations and film studios. The post war years saw directors who had no theatre background, such as Faruk Kenç, start to make films. The domestic market received a boost when taxes on Turkish-made films was reduced by 25%, in comparison to internationally made films. This gave local cinemas more incentive to screen local products.

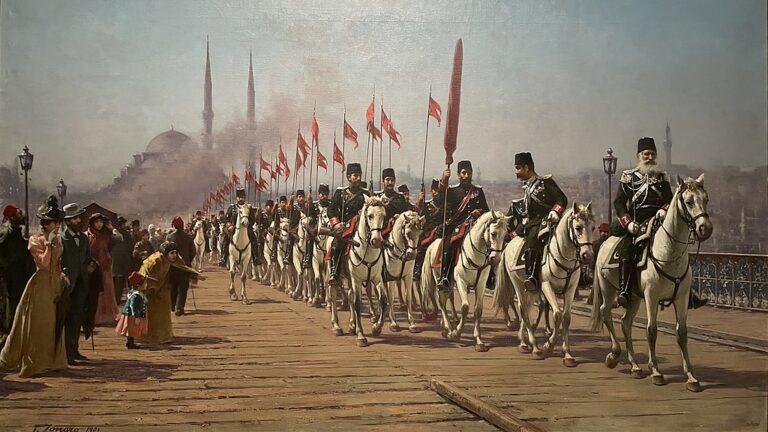

During the 1950s and 1960s the Turkish film industry began to experiment and expand its focus. They took important moments in Turkish history and captured them in dramatic form on celluloid, women and children began to take lead roles, and social issues, viewed through the lens of social realism, were portrayed on screen. However, by the second half of the 1960s quantity had begun to outstrip quality. Nonetheless some films were produced in this period that made stars who still draw audiences today, such as Türkan Şoray and Kemal Sunal. They emerged from Yeşilcam (Green Pine) Studios, named after Yeşilçam Street in the Beyoğlu district of Istanbul where many actors, directors, crew members and studios were based.

By the 1970s, television had seriously affected the number of cinema goers, yet this decade saw Turkish directors produce internationally acclaimed films. In particular Yilmaz Güney, Lütfi Akad and Tunç Okan made films that looked at the lives of people living outside big cities, and documented their everyday hopes and failures in films such as Zavallılar (The Poor Ones), Düğün (The Wedding) and Ötobüs (The Bus).

Turkish films looking at the effect of migration on the thousands of Turks who left their villages for Istanbul, and then Istanbul for Europe where they were guest workers, continued to be made in the 1980s. At the same time, films looking at internal unrest, the plight of workers in the south east and centre of the country, and other social content, were made. By the 1990s the number of films being made dropped significantly, as more privately owned television stations opened up, rerunning old films and producing their own very popular mini-series.

By the turn of the 21st century, local film makers and actors such as Yilmaz Erdoğan turned the spotlight onto the way traditional Turkish life was changing with the advent of modern technology. In his immensely popular film Vizontele, Erdoğan used the real life stories of villagers in Yıldıztepe in Erzerum to explore how the coming of electricity and therefore television, changed daily patterns, challenged friendships and disrupted lives.

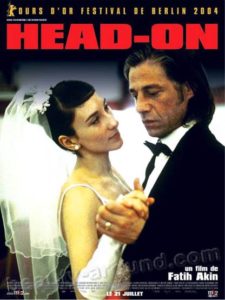

European born and influenced Turks such as Fatih Akin, Ferzan Ӧzpetek and Kutluğ Ataman brought a very new and challenging gaze into Turkish films. Their works such as Gegen die Wand (Head On), Cahil Periler (His Secret Life) and Lola und Bilikid (Lola and Billy the Kid) introduced non-Turkish audiences to a culture far removed from simple village life. They paved the way for directors such as Nuri Bilge Ceylan and his focus on the individual and existentialism in films such as Uzak (Distant) and Bir Zamanlar Anadolu’da (Once Upon a Time in Anatolia) and Semih Kaplanoğlu’s Yusuf Trilogy, Yumurta, Süt, Bal (Egg, Milk, Honey).

I hope you’ve enjoyed this brief introduction to the history of cinema and Turkish films. It’s far from complete and does reflect my own tastes and interests, so if there is anything you think I’ve forgotten, please feel free to add it in the comments below.

If you’d like more indepth information on Turkish films, I highly recommend Turkish Cinema: Identity, Distance and Belonging by Gönül Dönmez-Colin.

I think the appeal of Turkish Dizis in the foreign market lies largely in getting the right actors and a good storyline. They emphasize values that we would like to see revived in our own society and we can very well relate to the characters in the story.

I came to Turkey earlier this year for the first time because of my passion for Turkish dizi. When I got here, I realized there was much more to love about Turkey! ❤️