Turkish public hospitals – Up Close & Personal

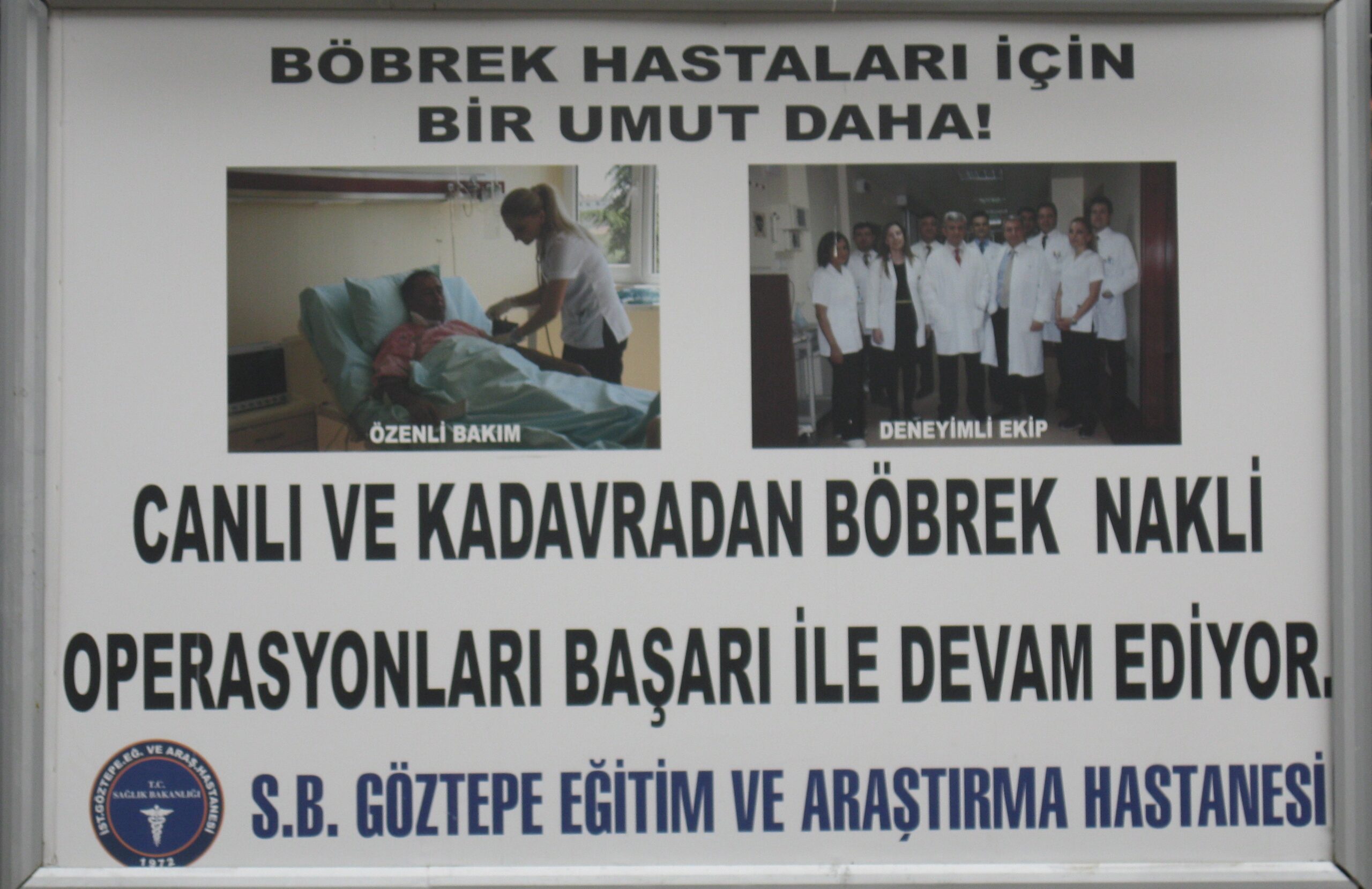

A look at the Turkish public health system

Back in 2000 my husband and I worked at an English college on Bağdat Street, run by a money hungry former military man with good connections but bad intentions. Thanks to him we had the dubious pleasure of visiting one of Istanbul’s many Turkish public hospitals as part of the process of getting a work permit. According to our charmless director we had to go to a public social security hospital, otherwise the bureaucracy in Ankara wouldn’t believe the results of our health tests were above board.

When we arrived and entered the foyer of the hospital, we were confronted by a simply enormous crowd of people. Everywhere I looked I saw people trying to squeeze their way past other people determined to stand their ground outside various doors while yet more people were pushing themselves through the clumps of people stuck on the stairs. I was reluctant to throw myself into the fray, so I looked to Kasım, the person assigned to get us through the day, for guidance.

Although he was always referred to as the school driver, he was more like a minder cum stand over man. I often saw him delivering bundles of money wrapped in newspaper to the director, and with his long moustache and hardened features he could look quite frightening. Nonetheless, he was always pleasant to us. Unperturbed by the seething mass of humanity around us he motioned us to follow him through the maze. We inched up a crowded stairway and when I looked back, I saw that every corridor and every waiting area was jam-packed.

The sheet of paper Kasım carefully held on to had about twelve different headings on it. All of them required a trip to a different department and a tick from a different pen. Hours after we first arrived we were each given a white plastic disposable cup with a number written on it.

Although it was nearing the lunch break we weren’t being offered tea but we did have to give urine samples. The women’s toilets were full of short round village women in headscarves, who all turned and stared when I walked through the door. Not only was I a foreigner, a yabancı, I had dark blue eyes and was wearing figure hugging, at least by their standards, Western clothes.

Their unblinking stares were unnerving so at first I just stood and watched proceedings, all the while clutching my plastic cup. I soon saw that the first hurdle would be getting into a cubicle. There was no queue to speak of, just lots of women milling around. Then it was first in first served. Even once the cubicles were occupied with the door locked (hopefully) and the red bar showing on the handle, the women would constantly shake the knob and ask was it full. It was survival of the fittest.

As I jockeyed to get closer I could see the toilets were of the traditional Turkish squat style. I pondered the practicalities of peeing into a plastic cup in a crouch position, while holding my handbag and coat above a floor I knew was going to be wet. I wondered how the Turkish women coped with their voluminous baggy pants, long thermal underwear, droopy cardigans and floor length coats.

Even though they had friends with them to hold their handbags and bit and pieces, we all shared the same problem as far as aiming accurately was concerned. If you squatted in the normal position you aimed downwards but wouldn’t be able to see the cup. If you shifted so you could see the cup, your flow would be horizontal and hard to capture.

However, before I could work out how to proceed, I had to get into a cubicle. Even though I’d been waiting for ten minutes, almost everyone who entered the room after me had either already bagged one, or was standing in front of me. Putting aside my middle class upbringing I deftly side-stepped a barrel-like woman, gently elbowed another away from the door and thrust aside a third to claim victory.

Once the door was tightly locked it was time to put the theory into practice. After some finessing I was able to hang my coat and handbag on the handle of the window. Settling into a comfortable position, I took some tissues from my pocket and did a ‘dry run’ of the procedure. I didn’t know how full the cup should be for the sample, but having no way of learning the answer I just went ahead regardless. Within a few moments I was finished.

Still squatting and now holding a half full or half empty, depending on your point of view, cup of urine, I had to work out where to put it while I adjusted my clothes. There were no shelves or ledges that I could use. Looking about the empty space I saw the only solution was to place a tissue on a dirty bit of broken tile, and carefully balance the cup on that.

Used to clinics where you could discreetly pass your sample to a nurse who wouldn’t look you in the eye I was very reluctant to go outside, cup in hand. Knowing Kasım would be waiting I felt really embarrassed. He had a well-developed sense of humour and I didn’t want to be the butt of one of his many jokes. The minutes ticked slowly by before I finally steeled myself for the walk back out into the corridor.

Luckily Kim exited the men’s at the same time and immediately captured Kasım’s attention. Holding out his cup, he asked if he wanted some tea. Kasım roared with laughter and I used the distraction to slip past him. I headed to the end of the corridor where a doctor was waiting with a trolley to collect our samples. When Kim joined me I asked him how he went.

“Well, I didn’t have any problems, but the guy before me must have. He came out trying to clean his cup up with a tissue,” Kim laughed and then added, “Turns out the black marker they use to number the cups isn’t waterproof after all”.

**********************

You can read about the rest of my experiences when I moved to Istanbul permanently in my memoir Exploring Turkish Landscapes: Crossing Inner Boundaries.

Love your true but funny first experience of public hospital Lisa. Mine was 1998 and in Marmaris so not quite as busy but still had crowds at every door pushing to go in first. 😊

The massive improvement in hospital services since 2000 is one of the reasons half the population (who couldn’t afford private health care) keep voting for the present government. We all remember these bad old days.