Turkish symbolism – meanings found in trees, graveyards and flowers

Turkey has a long and rich history easily seen in thousands of mosques, fountains, palaces and graveyards throughout the country. Library shelves groan under the weight of academic studies and research papers while internet sites and tourist guides abound, providing large swathes of information explaining important events and grand occasions. However within those places and behind the words on the page, there’s a whole other world of meaning in Turkish symbolism, expressed through the language of trees, flowers, Islamic and Ottoman symbols.

It’s common to see giant Oriental plane trees (çinar ağaçı in Turkish) in the gardens of major mosque complexes and elsewhere in Turkey. In Turkish tradition these trees represent greatness, permanency, superiority and sovereignty. In the past, whenever the Ottomans conquered new lands they planted a plane tree near water to seal their right to rule and even now a plane tree is planted when a major mosque is built. Plane trees can live for hundreds of years, and even after they die the trunks are left in place and protected. Consequently, centuries after the person or event they symbolise has been forgotten, the tree stump still stands.

Plane trees have long been revered in Turkish culture, but in Ottomans times they took their importance from a dream Osman 1 (the first Ottoman Sultan) is said to have recounted when he was a young prince. He was being educated by a dervish called Sheikh Edebali, famous for his purity and wisdom. One day while visiting his lodge Osman accidently saw Mal Hatun, the sheikh’s daughter, and fell immediately and madly in love. Unable to resist, he told the sheikh but Edebali refused to give his blessing due to the difference in their social positions.

One night, cast down with melancholy, Osman was just about to go to sleep when he spied a Koran on a shelf. Being pious and highly respectful of this holy book he took it down and started to recite the sura (sure in Turkish), the chapters in the Koran. He continued for six hours. Just before morning prayers were called he fell asleep exhausted, holding the Koran in his hands.

Osman dreamt he saw himself lying next to the Sheikh and watched as the full moon (symbolising Mal Hatun) rose up from the Sheikh’s chest high into the sky before sinking back into his body and disappearing. In place of the moon a plane tree began to grow, spreading its branches wide enough to cast a shadow over the entire horizon, before covering the whole of the world.

Beneath the tree Osman saw mountains carpeted with forests, rivers teeming with ships, verdant lands and fields bursting with crops. Everywhere he looked streams and fountains flowed through gardens full of cypress trees and roses. Valleys glittered with sparkling mosque minarets ringing with prayer while bird populated the tree, its leaves in the shape of scimitars, and filled it with their melodies.

Suddenly a great wind sprang up, turning the points of the leaves towards the great cities of the world, in particular Constantinople. Resting between two sea and two continents it looked like a diamond set between two sapphires and two emeralds, a ring worthy of a great empire. In his dream Osman saw himself putting the ring on his finger, then he woke up.

When Osman told Sheikh Edebali of his dream, he interpreted it as a good omen of Osman’s honour and power and told Osman Allah would give him and his progeny sovereignty, and that his son would rule the whole world. The sheikh no longer opposed Osman marrying his daughter and gave his blessing for Osman and Mal Hatun to be wed.

There are many well-known places connected to plane trees in Istanbul and Turkey. In the courtyard of the Atik Valide Mosque in the Uskudar neighbourhood of Istanbul a large plane tree grows on either side of the şardivan, the fountain where worshippers perform their ablutions before prayer. Further along the Bosphorus, on the same side of the city, the Çınaraltı Tea Gardens take their name from an enormous plane tree that dominates a small square bounded by water on one side and Hamdullah Paşa Mosque (also known as Çınarlı Mosque) on the other.

While the tea gardens only date to 1968, the tree is more than 780 years old. Time hasn’t always been kind to it but metal props help the majestic branches stand proud and cast their shade over tea drinking locals. Every November and March the branches are carefully pruned and in June when the branches are dry, new splits in the trunk and limbs are cleaned and sealed with pine tar. Structural cracks are bound together with stainless steel wires. Centuries old plane trees can also be found in other parts of Istanbul, such as Eyüp, Beyazit Square, Beykoz and Emirgan.

Further afield, in Bursa, they’ve adopted plane trees as the symbol of the city. Every plane tree in the city is numbered and registered with the department of public works. Incredibly, over in Yalova, when the branches of a plane tree encroached on the walls of a mansion, the owner of the building had it moved, rather than cut the tree. The person in question was Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, no ordinary man. He was the founder of the Turkish Republic and the mansion was built on his property, Baltacı Farm, in 1929.

Ataturk tasked Yusuf Ziya Erdem, the Director of Scientific Affairs at the Istanbul Municipality (which administered Yalova at the time) with moving the building. Erdem worked alongside chief engineer Ali Galıp Alnar and other technical staff. They came up with the idea of digging under the foundations and mounting the building on tram rails. Once this was completed they were able to relocate Ataturk’s house five metres to the east. As a result of this endeavour the structure is now known as the Yürüyen Köşk, the Walking Mansion.

Turkish culture also recognises cypress trees as having important meaning. In ancient times those in the shape of minarets were understood as the tree of life, symbolising abundance and plenty. Their roots reach deep into the earth, a sturdy upright trunk stands tall above the ground and the branches reach up to the sky.

These three things create a trinity evoking birth, life and the desire to reach the heavens. They are evergreen, symbolising immortality, so cypress are often planted in graveyards. However there’s also a practical reason for this. Cypress resin is highly fragrant and contains numerous chemicals, including ammonia that masks the smell of the dead. The Egyptians used cypress wood in embalming processes to prevent bodies from spoiling and enable them to cross safely to the next world.

In Istanbul cemeteries, many Ottoman tombstones, particularly the stones at the foot of women’s graves feature the tree of life motif as well as the cypress motif. The presence of a cypress tree on a gravestone signifies succumbing to one’s state and to the will of God. However when one cypress tree was carved within another it meant a woman had died giving birth to a girl.

Cypress trees are also valued for the sounds they make. A verse in the Koran states, “All living and non-living beings on earth utter the name of Allah in their own languages”. Muslims believe when the wind blows through the branches of cypress trees in graveyards making the leaves rustle, the noise is like a dervish at prayer uttering the word “Hû”, meaning “Allah”.

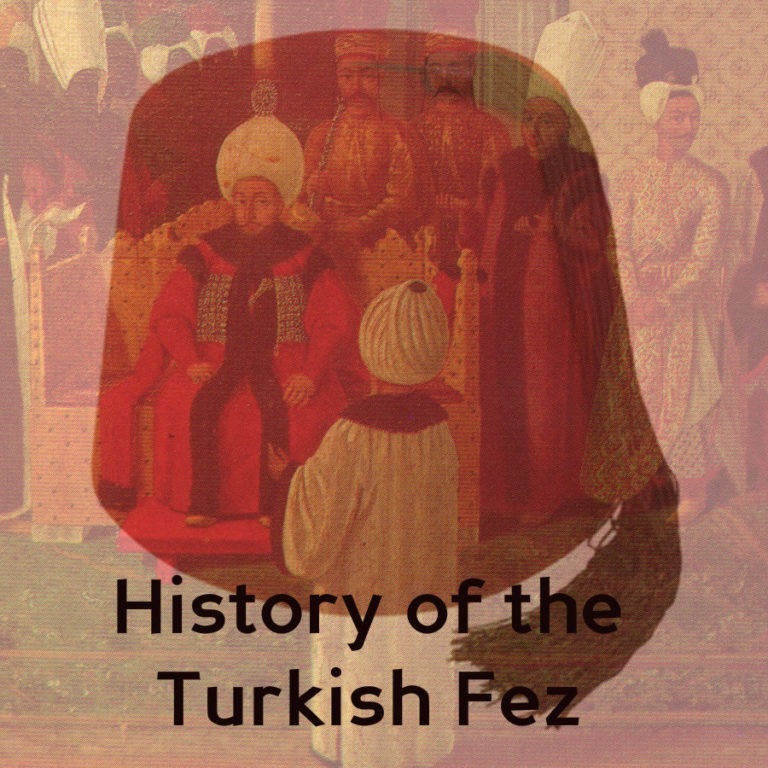

Far from being morbid unhappy places, Turkish cemeteries, particularly those in Istanbul, are elegant tree lined oases, perfect for solitary contemplation. Despite the quiet they are alive with communiques as long as you know how to read the symbols used on the headstones. Early gravestones take the form of a simple pillar inscribed with Ottoman Turkish topped by a stone turban if the person were a man, and a flower if a woman.

Over time women’s graves became more elaborate, etched with floral displays, earrings, brooches and necklaces. From the beginning of the 19th century, decorative motifs were also added to headstones for male graves. In general men’s tombstones were more earthly, and mainly decorated with headgear indicating their profession and rank.

In Ottoman times certain flowers, plants and symbols had special meanings. The most well-known of the flowers is the tulip. The Ottomans regarded tulips as holy because both the word Allah and the Arabic word for lale (Turkish for tulip) have the same numerical value in the EBCED system. In this system of calculation, named after the first four letters in the traditional Arabic alphabet EB-Ce-D, each letter has a specific value.

Decoding them allows the hidden meanings of words, phrases and sentences to be revealed. In the EBCED system both Allah and tulip words have the numerical value of 66, the number of Allah. A tulip on a gravestone symbolises the unity of Allah but when depicted upside down it indicated the occupant was a young girl who had died unmarried.

Roses often appear on Ottoman gravestones too. They were originally cultivated in hasbahçe, private gardens belonging to the sultan, such as Gülhane Park, once the private property of Topkapı Palace. Roses were first grown there during the period of Sultan Mehmed II and used to make rose water and gülbeşeker (rose jam) for the palace. An upside down rose signalled the same as an upside down tulip, but placed upright, it stood as a symbol of love for the Prophet Muhammed. A broken rosebud marked the death of a female family member. If a woman was engaged when she passed away, her gravestone had a bridal gown sculpted draping over it.

Numerous other symbols were used to create a sort of biography of the deceased, too many to cover in one post, but here are a few. Grapes connoted wealth and abundance, a mosque piety, and date trees the ascent to heaven. A dagger meant the occupant had been murdered or died young as the result of an epidemic. The Tree of Life indicated the deceased was of aristocratic origins while the Wheel of Fortune recognised the person had live in agony.

Flowers and trees were used to convey hidden messages amongst the living too, which you can read about in more detail in my post on flowers and the Judas tree in Ottoman and Turkish culture.

********************

I hope you’ve enjoyed this post on Turkish symbolism and it helps you get the most out of your next trip to Istanbul. If you’re in the process of planning your visit to Turkey, here are some helpful tips.

For FLIGHTS I like to use Kiwi.com.

Don’t pay extra for an E-VISA. Here’s my post on everything to know before you take off.

However E-SIM are the way to go to stay connected with a local phone number and mobile data on the go. Airalo is easy to use and affordable.

Even if I never claim on it, I always take out TRAVEL INSURANCE. I recommend Visitors Coverage.

I’m a big advocate of public transport, but know it’s not suitable for everyone all the time. When I need to be picked up from or get to Istanbul Airport or Sabiha Gokcen Airport, I use one of these GetYourGuide website AIRPORT TRANSFERS.

ACCOMMODATION: When I want to find a place to stay I use Booking.com.

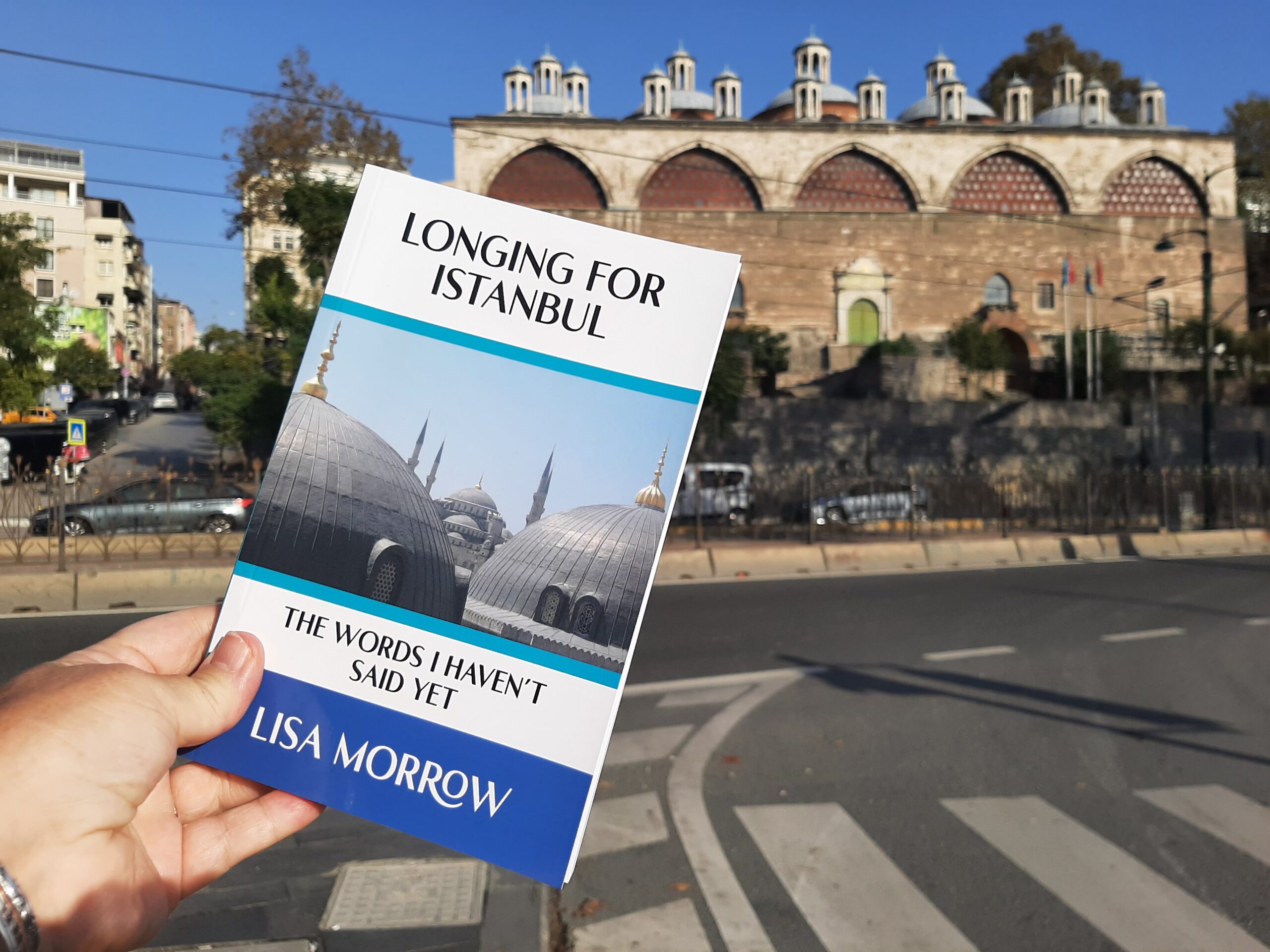

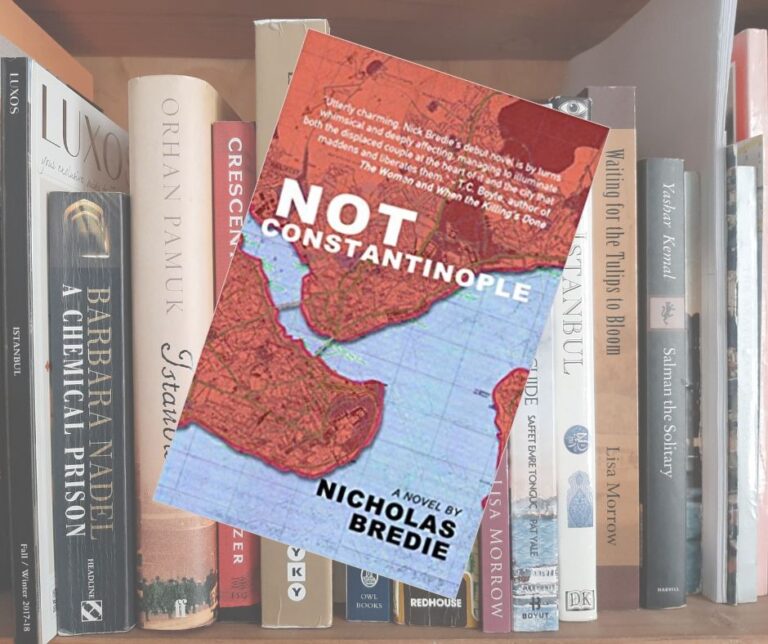

CITY TOURS & DAY TRIPS: Let me guide you around Kadikoy with my audio walking tour Stepping back through Chalcedon or venture further afield with my bespoke guidebook Istanbul 50 Unsung Places. I know you’ll love visiting the lesser-known sites I’ve included. It’s based on using public transport as much as possible so you won’t be adding too much to your carbon footprint. Then read about what you’ve seen and experienced in my three essay collections and memoir about moving to Istanbul permanently.

Browse the GetYourGuide website or Viator to find even more ways to experience Istanbul and Turkey with food tours, visits to the old city, evening Bosphorus cruises and more!

However you travel, stay safe and have fun! Iyi yolculuklar.

Jazak’Allah Khair! Thanks a lot! This is a very well-researched and detailed article!

Best regards from Chitral, Pakistan. We have lots of çınar ağacı trees here as well. They are quite old and represent aristocracy in our culture.

I really enjoyed yout article. Please write more about the Ottoman culture.

Hi Junaid, Thank you for your kind feedback. I’m glad you like my article and also like the trees as I do. It’s interesting to know they’re important in Pakistan too. I write about anything in Turkey that grabs my interest. If you want to know what it’s like to live here you should read my books too. I think you’d like Exploring Turkish Landscapes: Crossing Inner Boundaries.

I have seen some beautifully engraved tombstones still containing various color applications piled up and dumped on the side of the road in Iraklion, Crete about 60 years ago. Having admired the designs on the white marble monuments till then, I had not realized that originally they were full of colors -reds and greens, etc. Those that have been exposed to the weather for centuries they have lost them unfortunately.

Yes, when the gravestones were fresh and new the colours must have been wonderful.

I would recommend the cemetery in Rumeli Hisar, Istanbul, just next to Bosphorus University. It’s on a beautiful road, (Aşıyan Yol) and has intriguing headstones 🪦

Thanks for the suggestion. I’ll add it to my list of places to visit.

Do you have any favorite cemeteries that you recommend visiting? Also, there is some history of building on top of cemeteries. Given the building boom all over İstanbul, do you know if we have lost cemeteries die to building pressure?

Great article by the way. Would love for you to write more about Gülhane Park. Was simultaneously saddened, for me, and happy, for them, that they relocated the animals.

For cemeteries to visit I’d recommend the tombs in the grounds of Şehzade Mosque in Fatih, Yahya Efendi’s Kulliyesi in Besiktas and of course Haydarpasa Cemetery (see my post about this) in Uskudar. Karacaahmet Cemetery is worth a visit for the sheer size. I am yet to enter the non-Muslim parts there but they look tempting. All of them are marvellous both for the graves they contain and their locations. I know the remains from the Mashlak and Osmanieh Muslim Cemeteries were moved to Zincirlikuyu Cemetery in 1961 when these cemeteries could no longer be maintained. Other than that I don’t know if other cemeteries have been lost. I also remember the zoo at Gulhane and share your feelings. It was hard on the animals but many children had an opportunity to see animals close up they might not otherwise have had. I’d love to write more on the park one day. Maybe when I finish my latest book, sell my article on dogs and Islam, research a piece on the YMCA? So much to do and so little time!

I found your latest article exciting and full of interesting information. I’ve never managed to pass a graveyard without taking a walk around the graves and stopping to read the inscriptions, admire the decorations and wonder about the individual buried there.

I live in Osmangazi, Bursa, so am very pleased you took the time to mention our lovely Planes, they are quite remarkable as are our Ottoman graveyards.

Thank you so much for taking the time to comment. I’ve only been to Bursa once (years ago) and had a trip planned for 2020 but well, you know. I hope to go this year and will definitely look out for the plane trees.

Thanks, Lisa! This is very interesting! I saw the plane trees in Istanbul but did not know about their symbolism. Next time I will see them in a different light.

I’m pleased you found it interesting. It hope it gives you a deeper understanding on your next visit.